- PII

- S013216250016790-2-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S013216250016790-2

- Publication type

- Article

- Status

- Published

- Authors

- Volume/ Edition

- Volume / Issue 9

- Pages

- 242-256

- Abstract

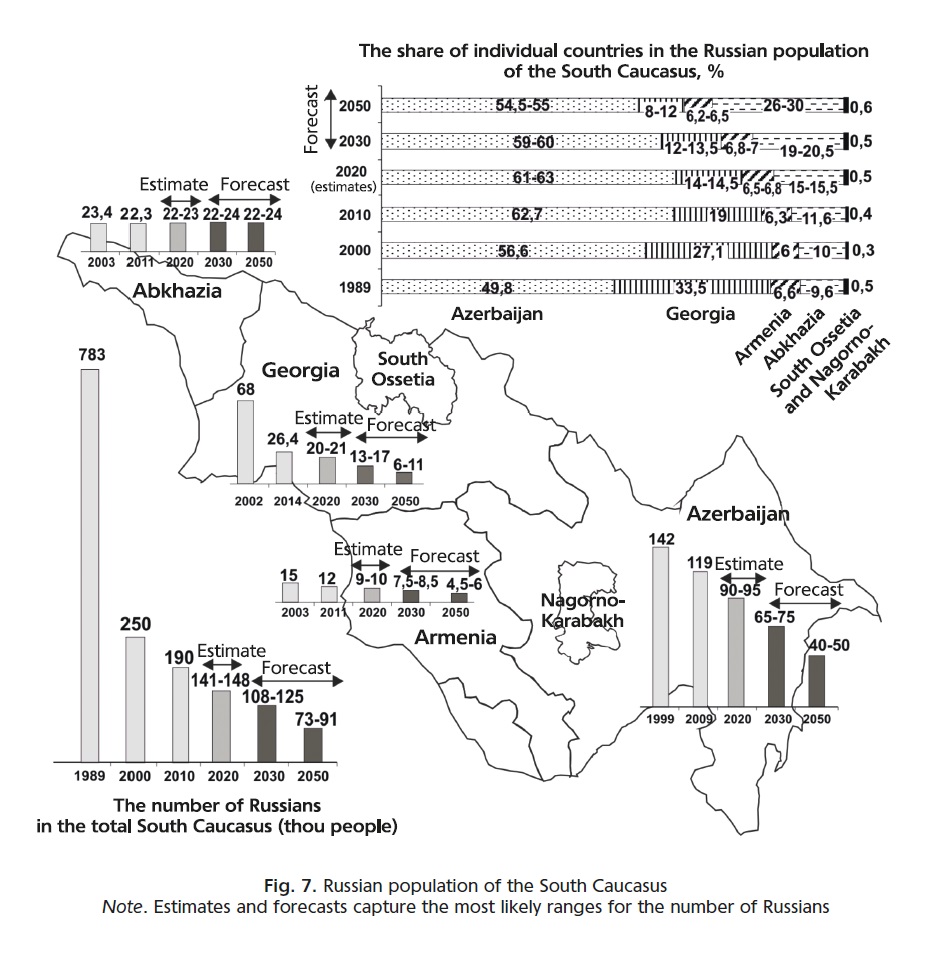

The collapse of the USSR sharply accelerated the depopulation of the South Caucasus, which fell from 783,000 to 140,000-148,000 people during the 1990s-2010s. The main demographic losses were due to outflows into Russia. The decline in the number of Russians was widespread and was accompanied by a serious deformation of their age and gender structure, with a noticeable predominance of women and older people. A noticeable part of the region’s settlement net (with the exception of Abkhazia) has lost its permanent Russian population. The epicenters of the Russian ethnic presence remain the capitals, and in rural areas − some settlements founded by Old Believers in the imperial period. The transformation of Russia into a guarantor of security for regional states (Abkhazia, South Ossetia) slowed the rate of loss of the Russian population, while confrontation with the Russian Federation (Georgia) markedly accelerated it. By 2050, the number of Russians in the region could decrease to 70-90 thou people. Baku will remain their largest medium. However, if current trends persist, in 30-50 years the Russian community of Abkhazia could become comparable in size to the Baku community. These two groups could comprise 85%-90% of the Russians in the South Caucasus in midcentury (47% in 1989). As the old-age communities continue to shrink, the prospects for the ethnic presence of Russians in the region will increasingly correlate with the size of the tourist flow and the size of the group of Russians who own local real estate. Russian military units stationed in the region will play a prominent role as major centers of the Russian population in some countries. At the same time, all these groups will no longer represent diasporas, complexly rooted ethnic communities with a high level of internal communication and the capacity for sustainable self-reproduction.

- Keywords

- South Caucasus, Russian population, geodemographic dynamics, settlement pattern, gender and age structure, migration, assimilation

- Date of publication

- 27.09.2021

- Year of publication

- 2021

- Number of purchasers

- 6

- Views

- 469

Research objective and common reference. Russians have been one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the South Caucasus (hereinafter referred to as the SC) for 150 years (mid-19th–20th centuries). During 1850-1917, the Russian population of the region grew from 30,000 to 400,000, and reached 975,000 in 1970 [Kabuzan, 1996: 265, 266]. The expansion of the Russian ethnic presence in the SC was one of the main components of the imperial (and later Soviet) project for the comprehensive integration of the region into the vital cycles of the Russian state. However, even in the post-Soviet period the geo- and sociodemographic indicators of the Russians of the SC remain an important indicator of the region states preservation in the Russian geocivilizational space. An independent aspect represents the geodemographic and settlement dynamics of the Russian population of unrecognized and partially recognized polities of the SC, allowing us to clarify the role of the sociopolitical factor in the preservation and reproduction of Russian communities in the region.

Various aspects of geodemographic, settlement and gender – age dynamics of the Russian population of the post-Soviet space have been in the focus of attention of the academic community since the early 1990s. Nevertheless, the Russians of the SC have become the object of research quite rarely, although the difficulties of their complex adaptation to new conditions of life were almost maximal (this is indicated by the rate of depopulation). Among the complex studies of the Russian population of the SC in the 1990s, we should mention the monograph by S.S. Savoskul [2001: 315-343], as well as works by N.M. Lebedeva [1995] and A.S. Yunusov [2001].

In the last 10-15 years, the activity of research in this scientific direction has decreased even more. In the literature, there are practically no publications devoted directly to the geodemographic dynamics of the Russian population of the region and its individual states. Some aspects of this problem are touched upon in articles that discuss general ethnodemographic processes in the modern SC [Kamakhia, 2007; Masaki, 2018; Lachenova, 2006]. However, it is obvious that this topic needs a more detailed study.

As an information base for the geodemographic analysis of the Russians in the SC can be used the data from the national censuses of the states in the region, which, however, differ significantly in the completeness of their ethnodemographic sections (Table).

Table

Censuses in the South Caucasus, 1999-2019

| State | 1999 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2005 | 2009 | 2011 | 2014 | 2015 | 2019 |

| Azerbaijan | • | • | • | |||||||

| Armenia | • | • | ||||||||

| Georgia | • | • | ||||||||

| Unrecognized and partially recognized states | ||||||||||

| Abkhazia | • | • | ||||||||

| Nagorno-Karabakh | • | • | ||||||||

| South Ossetia | • | |||||||||

Given that five to ten years have passed since the last censuses in the countries of the region,1 analytical procedures will be needed to assess the current demographic potential and geography of the Russian population. A much more difficult task is to perform geodemographic forecasting. Nevertheless, under certain conditions it is possible. Such a calculation should be oriented to obtaining the most probable range. At the same time, the forecast should take into account geodemographic trends that developed during the 1990s-2010s into a dynamic ‘rut’, which is very likely to continue in the future. The availability of data on the gender and age structure of Russian communities makes it possible to calculate the natural component of their future demographic dynamics using the age shifting method (such information exists in full for Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, and partially for Georgia and South Ossetia).

Dynamics of the Russian population in the South Caucasus in the post-Soviet period. The maximum level of ethnic presence in the region was reached by Russians in 1970-973 thou people. By 1989, this number decreased to 783 thou. However, the real ‘exodus’ of Russians from the SC began after the collapse of the U.S.S.R. In the 1990s, local Russian communities outpaced all other neighboring countries, except Tajikistan, in terms of depopulation. There were several reasons for such a mass exodus. Serious ethnopolitical and socioeconomic problems, typical for the entire post-Soviet space, were seriously aggravated by interethnic conflict. In fact, all the newly formed states of the SC found themselves in the early 1990s involved in military confrontations, which determined a rapid increase in the migration of Russians from the region. During 1989-1995, 55% of the Russian population left Armenia, 43% left Azerbaijan, and around 40% left Georgia [Savoskul, 2001: 321]. By the beginning of the 21st century, the number of Russians in the SC had decreased to 250,000, almost returning to the level of 1900.

Intense depopulation continued in the 2000s and 2010s. The main demographic loss was still associated with the outflow to Russia. At the same time, as the number of Russians decreased and their age and gender structure became increasingly deformed, the natural factor began to play a more prominent role in these losses. By now, the Russian population in the region has decreased to 140,000-150,000.

Many geodemographic trends were similar for all Russian communities in the post-Soviet period, including widespread and persistent depopulation, concentration in capital cities, a gradual increase in the average age, and a tangible gender imbalance. However, there were also certain country specifics that created opportunities for different variants of further demographic dynamics. The nature of relations between the states of the region and Russia played an important role in increasing this scenario variability. Thus, the geodemographic perspectives of the Russian population in each of the SC countries (including unrecognized/partially recognized) need to be analyzed independently. Since the comprehensiveness of modern ethnodemographic statistics varies markedly across the countries of the region, it is logical to begin the study with the community about which the most information is available.

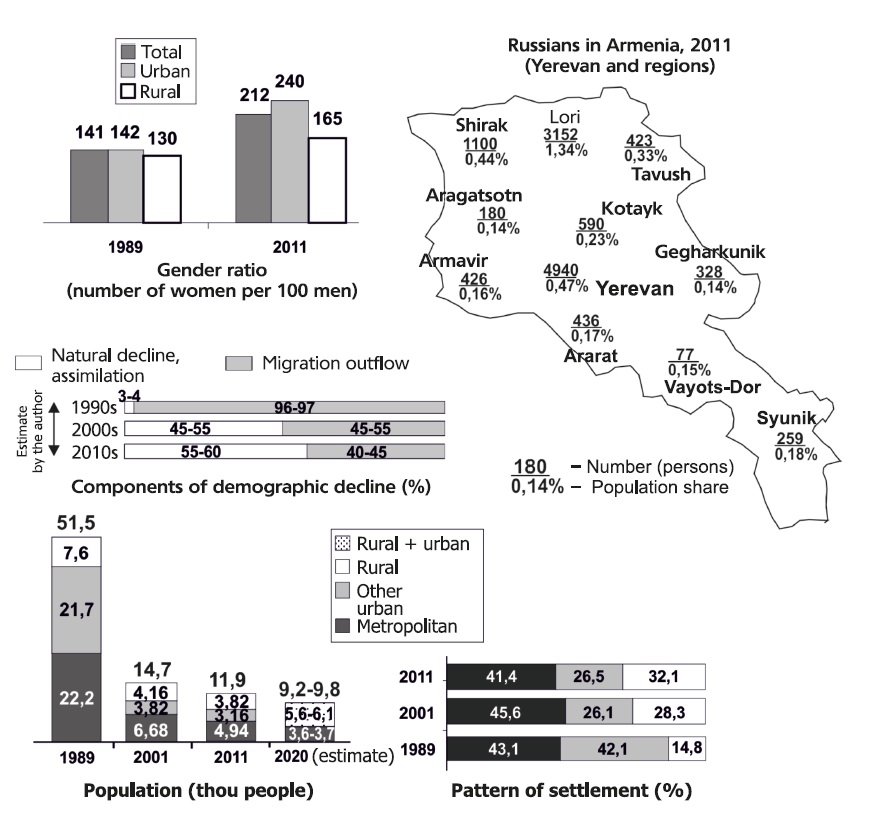

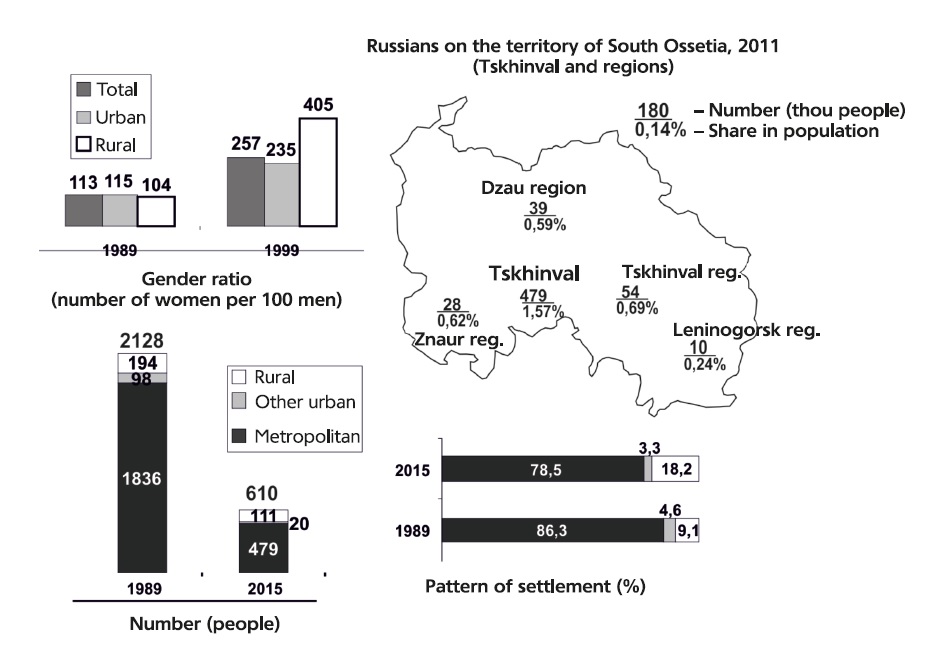

Armenia. Even during the Soviet period, Armenia stood out from the Soviet republics by the minimal presence of Russians. At its demographic peak their number was 70.3 thou people (1979). By the time of disintegration of the U.S.S.R. (early 1992) this number decreased to 41-42 thou people and in the mid-1990s it was 24-25 thou (calculated according to [Savoskul, 2001: 341]). The 2001 census recorded 14.6 thou Russians in Armenia. Consequently, the most significant part of the depopulation process fell within the first post-Soviet decade and was associated with migration − it accounted for 96%-97% of all demographic losses (Figure 1).

The rate of loss differed by pattern of settlement system. The number of Russians in Yerevan has decreased by 3.3 times in 1989-2001. The number of Russians in other Armenian cities has decreased by 5.7 times. The rural Russians were much more stable; the old inhabitants who settled in the SC during the Russian Empire, were the majority among them.

The gender imbalance, which had already been felt in the Soviet period, increased considerably. In 2001, there were 249 women for every 100 Russian men in Armenia and the average age of the population went up to 45 years (47.6 years for city dwellers). The combination of these two vectors of deformation of the gender and age structure led to a sharp increase in the proportion of older (over 60 years old) women: in 2001, they accounted for about a quarter of the Russians in Armenia. A significant portion of them had ‘titular’ husbands, which was the main reason why they refrained from migrating in the 1990s.

By the beginning of the 2000s, the most adapted part of the Russian population who did not want to (were not able to) leave the country, remained in Armenia. This circumstance determined its further geodemographic dynamics. In the first decade of the 21st century, the scale of the outflow decreases by an order of magnitude, and the natural factor connected (through interethnic marriage) with the assimilation of mixed offspring of Armenian-Russian families begins to play an increasingly important role in the depopulation of Russians.

Fig. 1. Russian Population of Armenia

In 2001-2011, the Russian population of Armenia decreased by 18.8% (to 11.9 thou people). In contrast to the 1990s, this reduction was not widespread. In half of the country regions, the number of Russians slightly increased or remained unchanged. But the demographic dynamics of the community in that period were determined by its two main epicenters: the Russians in Yerevan and the settlements in the Lori Region (several Molokan communities, including the largest ones in the villages of Lermontovo and Fioletovo). In total, these two epicenters accounted for over two-thirds of Russians in Armenia, and including the Russians of Gyumri, for about 75%.

A comparison of separate age generations of the Russian population according to the 2001 and 2011 censuses reveals the main decline among middle-aged (30-50 years old) and older (over 60 years old) people. In the first case, the main factor of the loss was migration, in the second case, it was increased mortality (natural factor). According to calculations, the depopulation of Russians in the 2000s was formed to a comparable extent by the outflow and natural loss.

The significant increase in the role of the natural factor also had positive consequences. Since a significant part of the loss was caused by old women, the growth of the average age of the Russian population has stopped and the gender imbalance has somewhat decreased. Nevertheless, in the early 2010s ‘older’ women continued to be the most significant group in the gender and age structure of the Russian community of the country, which, in addition to the imbalance, caused a huge age gap between the genders (the average age of Russian men in Armenia was 28.2 years, women − 51.3). Naturally, this disproportion had a negative impact on the reproductive performance of the Russian population.

The Armenian census scheduled for 2020 was postponed indefinitely due to the pandemic, and the dynamics of the Russian population in the 2010s can only be ascertained by expert evaluation. Given its gender and age structure, the most likely dynamic scenario for this period is that depopulation rates of the 2000s will be maintained. Some reduction in the outflow was supplemented by a growing natural decrease, associated not only with increased mortality of aged Russians, but also with a fall in the birthrate. The number of potential Russian ‘mothers’ aged 20-39 years old was expected to decline by 22% in 2011-2020 even without taking migration into account (from 1,750 to 1,370 persons). Given the average annual natural decrease of 10%-11% and some outflow, the number of Russians in Armenia could have decreased by 18%-20% in the 2010s. The losses in the community in the capital were most likely higher due to the high proportion of old people. By the early 2020s, there could be about 9,200-9,800 Russians in the country, including 3,600-3,700 in Yerevan, 2,500-2,600 in Lori province and 0,900-1,000 in Gyumri. About 2.2-2.5 thou people were settled in the rest of Armenia.

Further geodemographic prospects for the Russian community will be increasingly determined by natural dynamics. In 2021-2030, the number of Russian women of reproductive age will decrease by another 24% (from 1,370 to 1,040). Accordingly, the birthrate will continue to decline, including the fact that some Russian brides, by marrying members of the titular nation,2 begin to ‘work’ for the reproduction of the Armenian people.

The calculation of the natural dynamics of the Russian community using the age shifting method shows a 9%-10% decline in the 2020s and a 14%-15% decline in the 2030s and 2040s. Thus, without migration the number of Russians may decrease to 8,6-9 thou by 2030 and 6,3-6,7 thou in 2050. However, a complete cessation of the outflow is an extremely unlikely scenario, and keeping it even at the level of 3-5% over a decade can reduce these numbers by 1-1.5 thou people. The average age of Russians in Armenia could rise to 51 years by the middle of the century (43 years for men and 57.5 years for women).

The epicenters of the Russian community will continue to be Yerevan, Lori region, and Gyumri, but the ratio between them may change. By 2050, the number of Russians in the capital and Lori province will most probably equalize due to the accelerated attrition of ‘old’ Russians in Yerevan. The group of Russians in Gyumri, where the Russian military base is located, will be close to them. This makes it a center of attraction for Russians from all over Armenia. The rest of the country’s provinces (with the exception of the outskirts of Yerevan) may almost completely lose their small Russian population by mid-century.

The Russian ethnic presence in the country will also be linked to tourism, the importance of which may grow as the elderly population declines. In the late 2010s, 400-450 thou Russians visited the country annually [Comparative Statistics..., 2020]. Even if Russians made up only half of this tourist flow, there were several thou of them in Armenia at any given time, which is comparable to the size of the Russian community.

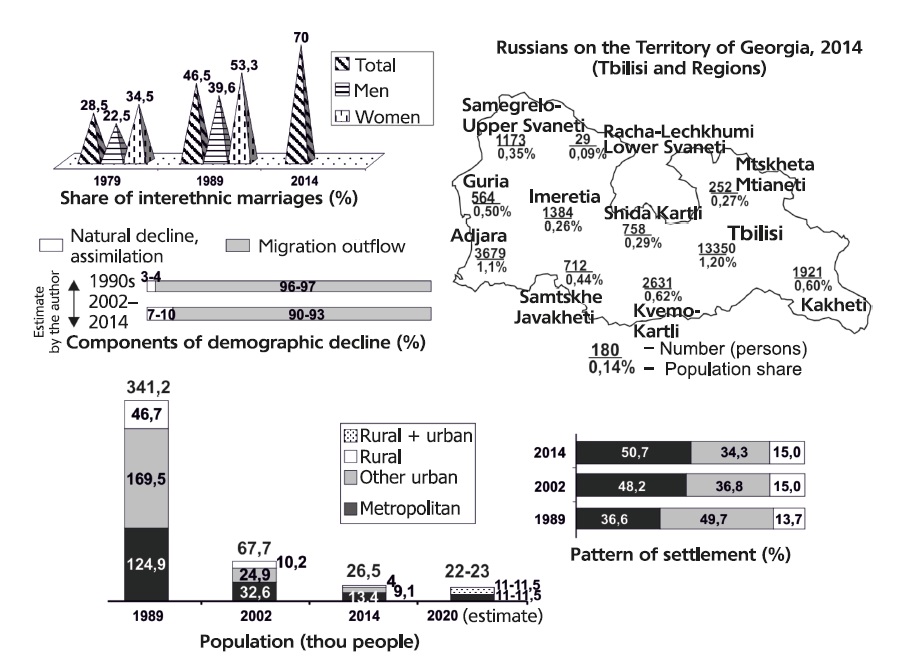

Fig. 2. The Russian population in Georgia

Georgia. In terms of the Russian population rate of decline in the post-Soviet period, Georgia surpassed all the neighboring countries except Tajikistan. And large-scale losses, not limited to the 1990s, continued into the first 10-15 years of the 21st century. In 2014, 26,400 Russians remained in the country (10% of the 1989 level). About half of them lived in Tbilisi, 35%-40% lived in a number of other centers (Batumi and Rustavi − more than 1,000 people in each, 400-500 in Kutaisi and Poti), 15% were settled in rural areas (Figure 2).

The gender and age structure of Georgia’s Russian population reveals even greater disparities than among Russians in Armenia. In the mid-2010s the share of people over 65 years old among them was 30.8% [Bruijn, Chitanava, 2017: 23] and taking into account the cohort of 60-64-year-olds it grows up to 39%-40% (10% more than in Armenia). At the same time, young people (15-29 years old) in Georgia accounted for only 13%-14% of local Russians [Eelens, 2017: 17]. The dynamic aspect was no less important. Of all notable ethnic groups in the country, it was Russians who in 2002-2014 had the fastest rate of aging [Bruijn, Chitanava, 2017: 23]. In the mid-2010s, their average age was 52-53 years, and the gender imbalance was comparable to that of the Russian community in Armenia. About 70% of family Russians in Georgia were in interethnic marriages (the maximum level among large and medium-sized diasporas of the country) [Hakkert, Sumbadze, 2017: 32], and the largest part of such families was represented by the ‘titular’ husband and Russian wife, and they actually fell out of the natural reproduction of the Russian community.

This indicates a very high rate of natural assimilation decline, which could reach 1.5%-2% per year at the beginning of the 21st century. However, the real average annual loss of Russians in Georgia was more than 20% in 2002-2014. Consequently, it was the outflow that continued to play an absolutely dominant role in their depopulation, although migration pulsed over a wide range, with a peak in the late 2000s (after the events of August 2008).

Prolonging the rate of decline from 2002 through 2014 by another decade (an extremely negative scenario) gives a figure of 10,000 to 11,000 Russians for the mid-2020s. By 2035, it could decrease to 4-5 thou people. Given that we are talking mostly about old people, this group risks almost completely disappearing by the middle of the century. But even if the rate of outflow has decreased since the second half of the 2010s, it will be extremely difficult for the Russian community to avoid a reduction of 15%-25% in each decade (natural decrease + some outflow) under any demographic scenario. With such a ‘soft’ rate of depopulation, 12-14 thou Russians will remain in the country by 2050, but more negative depopulation options are very likely.

As Georgia’s community of Russian old-timers shrinks, the Russian ethnic presence in the country will increasingly correlate with the scale of the Russian tourist flow and the size of the group of local property owners. In 2017-2019, 1.2-1.4 million Russians per year visited the country; depending on the season, 20,000-60,000 people stayed within the country at one time (calculated from [Comparative Statistics..., 2020]). In 2016-2019, more than 15 thou Russians bought housing or land plots here,3 i.e. during these four years about 8-10 thou Russians chose Georgia as their place of stay, if not permanent, then more or less frequent. With the normalization of the Russian-Georgian relations, tens of thousands of such Russians seem to be a realistic figure even in the most distant future. However, these people, who are not related to the Russian old-timers, will not be a diaspora. They will form a dispersed multitude whose geography is limited to Tbilisi and the coastal zone, above all Batumi and Kobuleti.

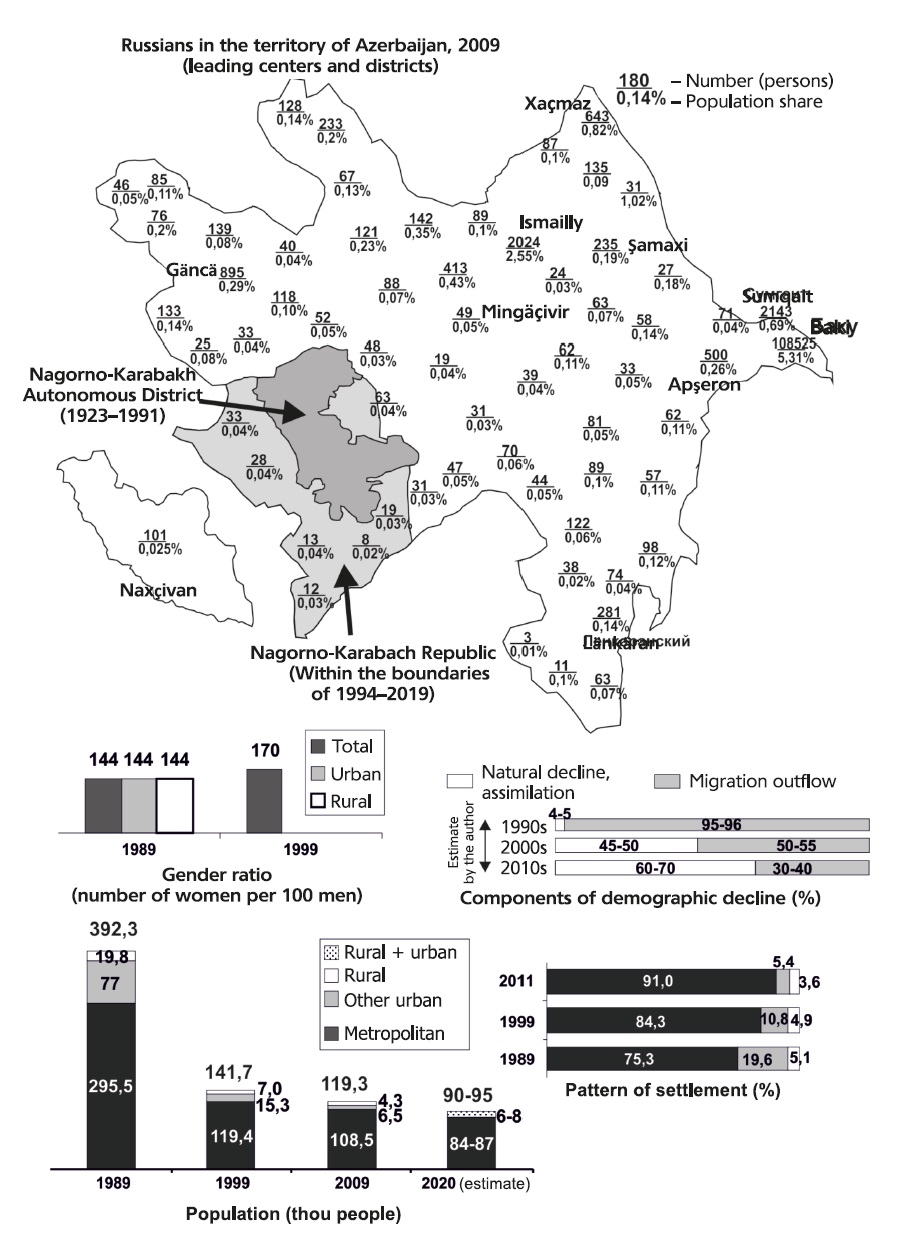

Azerbaijan. During 1989-2009, the number of Russians in Azerbaijan decreased 3.3 times, from 390,000 to 119,000. Despite large-scale depopulation, this is the best indicator among the three major states of the Southern Caucasus. A specific feature of the Russians in Azerbaijan is their ‘metropolitan nature’, which has been peculiar to them since the Soviet period (in the 1920s and 1980s, two thirds to three fourths of all Russians in the republic lived in Baku), but which has intensified in recent decades. In 1999, 84% of the Russian population of Azerbaijan was concentrated in the capital; in 2009, this number had already increased to 91%. Less than 11 thou Russians remained outside Baku, including 2,100 in Sumqayit and 0.89 thou in Ganja (Fig. 3). About 2 thou people lived in Ivanovka, a Molokan settlement (Ismailly district), which comprised about half of all rural Russians in the country.

At the time of writing, the results of the 2019 census had not yet been published, and we had to resort to expert estimates of the current demographic potential of Azerbaijan’s Russian population. The second decade of the 21st century turned out to be a period that was stable for the country both politically and socioeconomically, so the outflow of Russians to Russia, given its difficult situation in the 2010s, should have decreased. At the same time, natural losses in the Russian community were likely to increase. Already at the end of the twentieth century, the average age of Russians in the country was 41 years, and there were 170 women per 100 men [Yunusov, 2000]. In the 2000-2010s, the disparities in the gender and age structure should have increased markedly, since the small generation of the 1990s began to enter the period of reproductive activity in the 2010s.

The situation of the Russian community in Azerbaijan was complicated by the fact that here (unlike in Armenia) a significant gender imbalance affected the youth generations. In the group of 14-29-year-old Russians there were only 69 young men per 100 girls [Youth of Azerbaijan, 2020: 28]. Because of the shortage of Russian ‘suitors’ alone, about a third of young Russian women were forced into interethnic marriages. However, in addition to this, there were other factors that further increased the proportion of such families.

Fig. 3. The Russian population in Azerbaijan

There is every reason to believe that in the 2010s the rate of depopulation of the Russian community, compared to the beginning of the 21st century, at least did not decrease or even slightly increased, amounting to about 20%-25%. In this case, about 90-95 thou Russians could stay in Azerbaijan by 2020 and 92%-94% of them will probably live in Baku. In other words, the demographic future of the country’s Russians is primarily the prospects of their metropolitan group, whose further depopulation is inevitable, but its rate may vary markedly. Taking the above into account, the natural decline of the Russians in Baku in 2020s will hardly be lower than 12%-15% per year.4 Taking into account the outflow, even if it is reduced to 3%-5% over the decade, the depopulation over 2021-2030 will be around 15%-20%, and this demographic scenario can be considered positive.

In the future, as the Baku Russians age, the rate of their natural decline will increase and the scale of their outflow will decrease. Such a depopulation rate – 15%-20% per decade − seems a fairly plausible scenario until the middle of the century. As a result, even without a social force majeure, the number of Russians in Baku may decrease to 65-75 thou by 2030 and to 40-50 thou by 2050. In an ‘accelerated’ scenario this figure could be 1.5-2 times less.

The geography of Russians in Azerbaijan will continue to shrink due to the disappearance of local groups of dispersed settlement. In the late 2000s, in most rural areas of the country their size was limited to a few tens of people (0.04%-0.1% of the local population), and by 2020 these small groups could lose another ¼-⅓ of their size. Relative demographic stability in the post-Soviet period was demonstrated only by a number of old Molokan settlements, although even they were losing population quite rapidly: during the 2000s, the number of Russians in Ivanovka dropped from 2.5 thou to 2.0 thou. The same depopulation trend could very likely persist in the 2010s, but it is unlikely to prevent Ivanovka from increasing its share in the demographic potential of rural Russians to 55%-65% by 2020 and overtaking Sumqayit to become the country’s second largest center in terms of Russian population.

Thus, in the geography of Russian Azerbaijan, two epicenters of the settlement system are becoming more and more distinct: Baku for urban dwellers and Ivanovka for rural inhabitants. In the following decades this spatial peculiarity is likely to intensify. As the old-age population decreases, the Russian ethnic presence in Azerbaijan, as well as in neighboring Armenia and Georgia, will correlate more and more with the Russian tourist flow, which in the late 2010s amounted to 800-900 thou people per year. Depending on the season, 15-30 thou Russians stayed in Azerbaijan at a time (calculated according to [Comparative statistics..., 2020]), and the country has every opportunity to maintain or increase this indicator. At the same time, Azerbaijan (unlike Georgia) has not become an attractive place for Russians to purchase real estate (not counting ethnic Azerbaijanis with Russian citizenship).

The unrecognized and partially recognized states of the South Caucasus. As a result of armed conflicts in the post-Soviet period, three such entities emerged on the territory of the region: Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh. Despite a number of similarities, the geodemographic dynamics of their Russian populations have notable specificities.

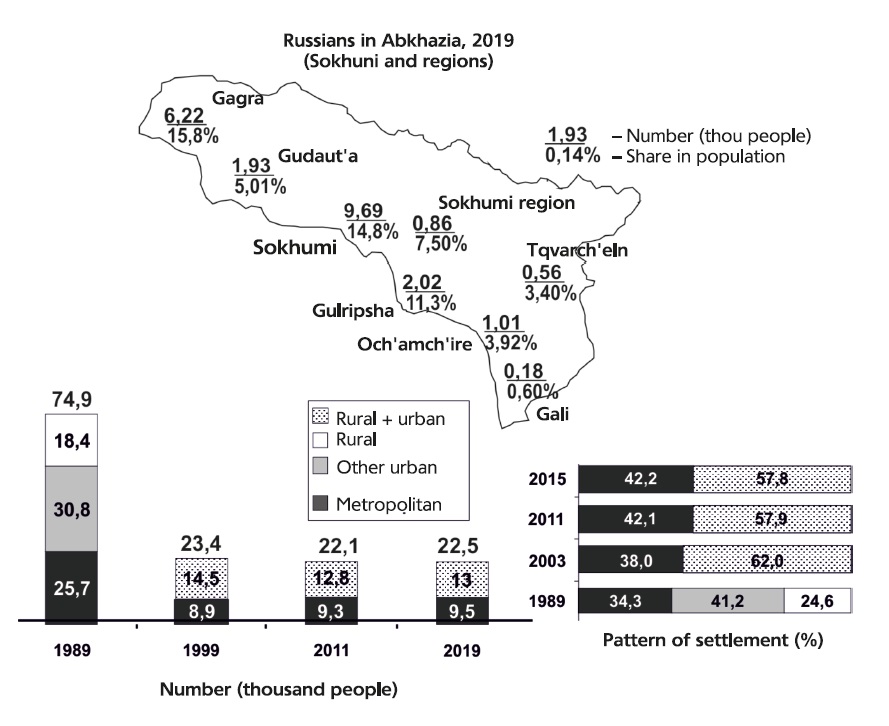

Fig. 4. The Russian population in Abkhazia

Abkhazia. The main depopulation of the local Russian community occurred during the Georgian-Abkhaz armed conflict in 1992-1993. On the whole, during the 1990s, the number of Russians decreased by 3-3.5 times from 75,000 to 20,000-25,000 people (Fig. 4), which is comparable to the rate of decline of the Russian population in Georgia. Nevertheless, by the end of the 20th century the size of the Russian community in Abkhazia had stabilized: 23,400 and 22,100 people in 2003 and 2011 respectively.5 A similar value is found in the results of the current demographic record in 2015-2019: 22.3-22.5 thou [Abkhazia in Figures..., 2020: 27-29].

The reliability of the current statistics of the republic is questionable, but there is no doubt that a number of significant factors work for the sustainable preservation of the Russian population of Abkhazia. Among them is the exclusive role of Russia as the guarantor of the republic’s independence, and Russian tourism as the main source of income for the republic’s budget and a significant part of the population. All this is certainly reflected in the attitude of the authorities and the titular community toward local Russians.

After Russia recognized Abkhazia’s independence in 2008, the prerequisites for a rapid increase of the Russian ethnic presence there have increased significantly. The main factors are natural and climatic attractiveness and the low price of local real estate. The main factors were the natural, climatic attraction and the low price of local real estate. At the same time, the growth of Russian homeowners throughout the entire subsequent period was significantly hampered by unregulated legislation on property acquisition by foreigners. The Abkhazian authorities were obviously deliberately reluctant to solve this problem for fear of transferring a significant part of the republic’s housing stock into the ownership of Russians. Another undesirable consequence could have been the rapid growth of the Russian population, which would have perceptibly changed the national structure of the small republic’s society. However, even in conditions of legal insecurity, the number of Russians buying real estate in Abkhazia was quite significant. Only the number of trials related to its purchase in the mid-2010s ranged from three to four thou,6 and the total number of Russians, homeowners (the group of ‘sporadic’ stay), could be many times greater, i.e. comparable with the permanent Russian population.

If we take into account the entire Russian tourist flow (from 4.3 to 4.8 million people annually in 2016-2019), we can talk about much larger values. Depending on the season from 100 to 200 thousand Russian tourists are simultaneously on Abkhazian soil (calculated according to [Comparative statistics..., 2020]), and Russians, based on the national structure of the Russian Federation, may constitute three quarters of this multitude, which makes them the most numerous national group of the ‘available’ population of Abkhazia. And from May to October, the Russians outnumber the rest of the population in the seaside area many times over.

These circumstances have an impact on the structures of everyday life, economic activities, sociocultural practices of the republican society and increase the socio-psychological comfort of the life of local Russians. In addition, the permeability of the border between Abkhazia and the Russian Federation significantly facilitates spatial circulation between the countries. Thus, the demographic dynamics of the Russian community in Abkhazia is primarily determined by migration, the scale of which is regulated by the authorities of the republic in accordance with the interests of the titular nation.

The most likely scenario for the demographic dynamics of the Russian population in the medium and long term seems to be fluctuating within the existing corridor from 22 to 24 thou people. Significant stability will obviously be demonstrated by the geography of their settlements, which mainly cover the coastal network of settlements with the epicenters in the Gagra and Sokhumi regions; in the last 20 years they together account for about 70% of the Russian population of Abkhazia.

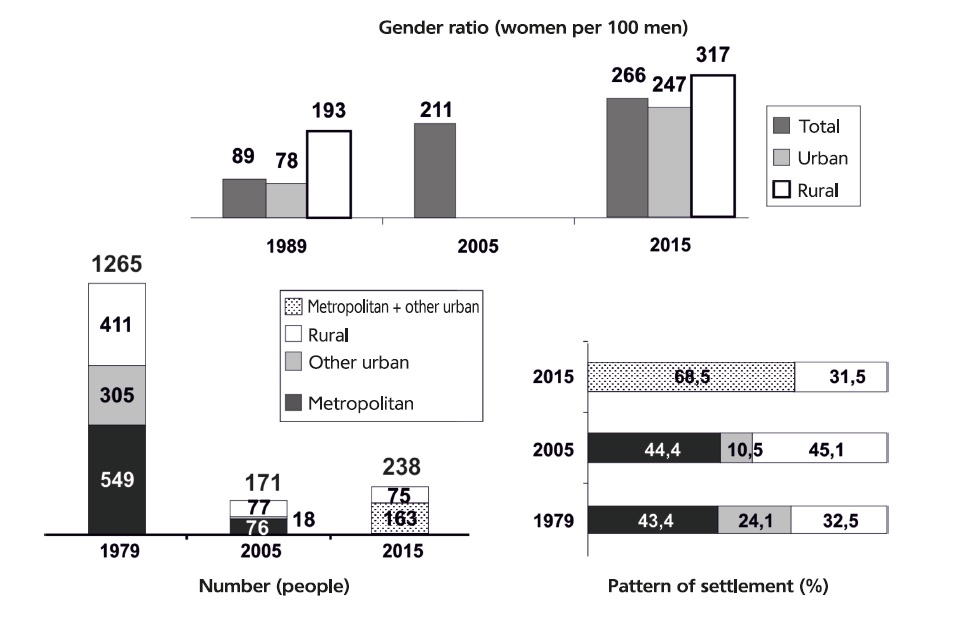

South Ossetia. The Russian population in South Ossetia has always been small. Reaching its peak by the early 1960s (2,380 people) it remained at the level of 2,000-2,100 in the last decades of the Soviet period. Armed conflict with Georgia and socioeconomic problems of the 1990s led to a drastic reduction in the number of Russians in the republic. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the size of the Russian community in the South Ossetia stabilized again, remaining at 500-600 people, with 75%-80% of them in the capital Tskhinval.

The 2015 census recorded 610 Russians in the republic, revealing an extremely high level of gender imbalance: 439 women and 181 men (Figure 5). The almost 2.5-fold female predominance was in itself a prerequisite for high interethnic marriage among the local Russian population, but its actual level in the South Ossetia turned out to be the highest. Only 13 of 213 (6%) married Russian women had a Russian husband, 180 (88.7%) had an Ossetian. The situation with Russian men in the republic was similar: only 13 out of 68 Russian husbands (19%) were married to Russians and 51 (75%) to Ossetians.

The exceptionally small percentage of monoethnic marriages among Russians in the South Ossetia indicates that virtually all such families have left the republic. Only the presence of a ‘titular’ husband/wife kept the family from leaving for the Russian Federation. Accordingly, all children, adolescents and youth groups of the Russian community of the South Ossetia are now represented by Russian-titular bi-ethnophores, and this is of central importance for its demographic future. Already in the medium term, the assimilation process may lead to an accelerated depopulation of the local Russian population. Under such a scenario, by the middle of the century the Russian population could decrease by 1.5-2 times, and then the Russian ethnic presence in the republic will be mostly limited to servicemen of the 4th Guards Military Base stationed in Tskhinvali and Djava, which is (and will remain) the main center of the ‘available’ Russian population in South Ossetia.

Fig. 5. Russian population of South Ossetia

Nagorno-Karabakh. The number of Russians in Nagorno-Karabakh reached its maximum in the late 1930s (2,100 people). In the post-war decades, this number gradually decreased until the second half of the 1980s, when a significant number of refugees, including Russians, from various centers and regions of Azerbaijan appeared in the autonomy. However, the growth, observed in the last years of the USSR, was short-lived: during the Armenian-Azerbaijani armed conflict of 1992-1994, the largest part of Russians left the region.

The nationwide census of 2005 registered only 170 Russians in the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (hereinafter NKR) of which more than 44% lived in Stepanakert (which corresponds to the figures of the late 1980s).7 The age and gender characteristics of this small group (its average age is 42.8 years; 69.5% are women) indicated a high probability of further depopulation, but in 2005-2015, the number of Russians in the NKR increased to 239 people, i.e. by almost 40% (Fig. 6). Almost all of the increase was in Stepanakert, while the number of rural Russians remained unchanged. Taking into account the natural decline, it was provided mainly by the migration inflow. Nevertheless, this did not change the negative dynamics of the age and gender structure of Russians.

Fig. 6. Russian population of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous District and the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic

In the mid-2010s, the average age of Russians in the NKR rose to 49.9 years, and the proportion of women rose to 72.7%. Almost a third of the Russian population of the republic were women over 60 years old, and there were only 0.56 children per Russian woman of active reproductive age (20-39 years old) (in the Russian Federation this indicator was 1.28). The main reason for such a low indicator is not the actual small number of children of Russian women in the NKR, but interethnic (primarily Russian-Armenian) marriages, as a result of which the bulk of children in such families were recorded by the census as part of the titular nation. Finally, the age structure of Russian women in the NKR indicated the most significant reduction of the birth rate in the future 10-15 years: in 2015 there were 50 of them at the age of 20-39, by 2025 this number should decrease to 31, and by 2035 − to 11. However, this downward trend does not take into account either the negative consequences of the second Karabakh war (September−November 2020), or the high probability of the migration outflow of some local Russians from the NKR.

Thus, the characteristics of the Russian population of Nagorno-Karabakh and the current realities of life in the republic will contribute to the rapid depopulation of the Russian community in the medium term. The only factor of its support is the Russian peacekeeping contingent stationed in the republic since November 2020. It is obvious that the servicemen will be, at least until 2025, the main group of the available Russian population in the NKR.

Conclusions. The collapse of the U.S.S.R. sharply accelerated the process of ethnic derussianization of the Southern Caucasus, already observed from the 1960s-1970s. The reduction in the number of Russians was widespread and was accompanied by a serious deformation of their age and gender structure, which is now noticeably dominated by women and people of older age. A large part of the region’s settlement network (with the exception of Abkhazia) has now almost completely lost its permanent Russian population. The epicenters of the Russian ethnic presence in the Southern Caucasus remain the capitals, and in rural areas some settlements founded by Old Believers in the imperial period. The transformation of Russia into the closest ally and guarantor of national security for regional politics (Abkhazia, South Ossetia) slowed or stopped the depopulation of the local Russian population, while the harsh confrontation of states in the region with Russia (Georgia) markedly accelerated it.

Fig. 7. Russian population of the South Caucasus

By the middle of the century, the number of Russians in the South Caucasus could decrease to 70-90,000 (Fig. 7). Baku will remain their largest population center. However, if the current trends persist, in 30-50 years the Russian community of Abkhazia may become comparable in size. By 2050 these two centers could have 85%-90% of all Russians in the Southern Caucasus (in 1989 47% of Russians lived there and in 2020 there were 75%-80% of them).

The region is one of the attractive destinations for Russian tourism. As the old-time communities shrink, it is with tourists and Russian owners of local real estate that the main prospects for maintaining the Russian ethnic presence in most countries of the Southern Caucasus may be connected, with Abkhazia and partly Georgia having the greatest potential in this regard (subject to the normalization of interstate relations with Russia). Russian military units (13,000 to 14,000 men) stationed in the region also play a notable role in maintaining the Russian ethnic presence in the Southern Caucasus. In the long run, they can remain the main core of the available Russian population in South Ossetia, Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. At the same time, it should be kept in mind that all these groups of temporary residents will not represent diasporas, i.e. complexly rooted ethnic communities with a high level of internal communication and the capacity for sustainable self-reproduction, and their geography will be limited to capitals, resorts and popular tourist routes, as well as military bases.

References

- 1. Abkhaziya v tsifrakh za 2019 god [Abkhazia in figures for 2019]. Lagvilava A., Sokhumi, 2020 (In Russ.)

- 2. Bruijn B., Chitanava M. Ageing and Older Persons in Georgia. NFPA Office in Georgia, Tbilisi, 2017. (In Engl.)

- 3. Eelens F. Young People in Georgia. NFPA Office in Georgia, Tbilisi, 2017. (In Engl.)

- 4. Hakkert R., Sumbadze N. Gender Analysis of the 2014 General Population Census Data. NFPA Office in Georgia, Tbilisi, 2017. (In Engl.)

- 5. Kabuzan V.M. Russkiye v mire [Russians in the world] // Blitz, Sankt Peterburg, 1996. (In Russ.)

- 6. Kamakhia M. Slavyanskoye naseleniye Gruzii [Slavic population of Georgia] // Tsentral’naya Aziya i Kavkaz. 2007. No. 4 (52). Pp. 152-165. (In Russ.)

- 7. Laschenova E.A. ‘Russkiy mir’ v Armenii [‘Russian world’ in Armenia] // Rossiya i sovremennyy mir. 2006. No. 3 (52). Pp. 225-231. (In Russ.)

- 8. Lebedeva N.M. Novaya russkaya diaspora: sotsial’no-psikhologicheskiy analiz [New Russian Diaspora: Socio-psychological Analysis]. Moscow: IEA, 1995. (In Russ.)

- 9. Mosaki N.Z. Etnicheskaya kartina Gruzii po rezul’tatam perepisi 2014 g [Ethnic picture of Georgia according to the results of the 2014 census] // Etnograficheskoye obozreniye. 2018. No. 1. Pp. 104-120. DOI: 10.7868 / S0869541518010086. (In Russ.)

- 10. Savoskul S.S. Russkiye novogo zarubezh’ya: vybor sud’by [Russians of the New Abroad: A Choice of Fate]. Nauka, Moscow, 2001. (In Russ.)

- 11. Sravnitel’naya statistika vyyezda grazhdan Rossii za granitsu v 2018 i 2019 godakh [Comparative statistics of the departure of Russian citizens abroad in 2018 and 2019] // Assotsiatsiya turoperatorov. February 13, 2020. URL: https://www.atorus.ru/ratings/ analitic_mrch/new/50476. html (accessed on May 28, 2021). (In Russ.)

- 12. Vsesoyuznaya perepis’ naseleniya 1989 goda: Raspredeleniye gorodskogo i sel’skogo naseleniya oblastey respublik SSSR po polu i natsional’nosti [All-Union Population Census of 1989: Distribution of Urban and Rural Population of the USSR Republics by Gender and Nationality] // Demoskop-Weekly. URL: http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/resp_nac_89.php (accessed on May 30, 2021). (In Russ.)

- 13. Youth of Azerbaijan: Statistical Yearbook. State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Baku, 2020. (In Engl.)

- 14. Yunusov A.S. Etnicheskiye i migratsionnyye protsessy v postsovetskom Azerbaydzhane [Ethnic and migration processes in post-Soviet Azerbaijan] // Materials of the international conference ‘Problemy migratsii i opyt yeye regulirovaniya v polietnicheskom kavkazskom regione’ [‘Problems of migration and experience of its regulation in the multi-ethnic Caucasian region’]. 2001. URL: http://chairs.stavsu.ru/geo/Conference/c1-67.htm (accessed on May 17, 2020). (In Russ.)