- PII

- S013216250016785-6-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S013216250016785-6

- Publication type

- Article

- Status

- Published

- Authors

- Volume/ Edition

- Volume / Issue 9

- Pages

- 198-207

- Abstract

The article presents results of an empirical study by FCTAS RAS in order to analyze the spiritual state of modern Russian society and its ideas about itself, which should be considered as a special nonmaterial factor for its development. The study was conducted in March – April 2021 in a series of studies aimed at creating a kind of “sociological portrait” of modern Russian society, viewed through the prism of its self-esteem and self-image. In this article, the authors focuse on a facet of this sociological portraying, i.e. on the opinions of Russians about the ways of their country’s development, assessments of the historical productivity of this path and, in this regard, their personal prospects, as well as on what they would like to see their country to be in the future. The authors analyze peculiarities of the perception of the arrow of time in the Russian mentality, characterize emotional tone of Russians’ thinking about the future, characterize dynamics of the gradually increasing demand for change in Russian society, and examine in detail the views of the population of the country about what tasks currently facing Russian society are priorities and what ideas could unite Russians on the way to the future. Special attention is paid to the opinion of the Russian population about its relations to the West and the East. Basing on the results of empirical research, the authors state that Russian citizens perceive their country as an independently developing civilization and in this context reject mechanical following of Western models and recipes. In conclusion, the article examines the features of the political segmentation of the Russian society. An explanation is offered for the idea that, despite the fact that there is a demand for change in Russian society, a majority of citizens tend to support the current government and, despite all its shortcomings, would not want to change it by another one, at least now.

- Keywords

- Russian society, Russian civilization, sociological portrait, image of the future, development model, social changes, political process

- Date of publication

- 27.09.2021

- Year of publication

- 2021

- Number of purchasers

- 6

- Views

- 304

"Sociological portrait" as the purpose of the study. One of the characteristic, one might say, "trademark" features of Russian scientific culture is a special interest in conducting research in the genre of "portrait" sociology, the specific task of which is an integral description of various social worlds and specific societies [Andreev, 2017]. Such works have become a response of the Russian sociological community to an urgent public inquiry - to sort out again who we are, what we are striving for, and how, based on this, to build a new strategy for the country's development, which, on the one hand, does not contradict the mentality and historical memory of Russians, and, on the other hand, fully meets the challenges of the 21st century.

The methodological groundwork for a "portrait" sociology was already underway in Soviet times, beginning at least with a detailed study of the informational and sociocultural environment of a typical Soviet industrial city led by B.A. Grushin [Mass Information..., 1980]. Later on, the tradition of such sociological descriptions was expanded and enriched in the works of M.K. Gorshkov, N.I. Lapin, J.T. Toshchenko, M.F. Chernysh, V.K. Lavashov, V.I. Fedotova, V.V. Kozlovsky, N.E. Tikhonova, F.E. Sherega and other Russian scientists. The leading role in the development of this direction continues to be played by the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, as well as other scientific institutions, which became part of the RAS FCTAS (Federal Center of Theoretical and Applied Sociology) in 2017.

This article presents the results of another such survey. The sociological survey, which formed its empirical basis, was conducted in March 2021 by questionnaire polls according to the standard for such studies: the sample is of quota-type, representative of the socio-demographic structure of the country's population; the sampled population size is 2000 respondents. The survey covered 22 constituent entities of the federation representing 11 out of 12 territorial and economic regions of the country (except Kaliningrad region). Respondents were offered to answer questions concerning their personal situation and the situation in the country as well as to describe their own social and political activity and actions that they were taking or were going to take to protect their interests. Value preferences were probed through questions involving a choice between two alternative judgments. For example: "People should limit their personal interests for the sake of the interests of the country and society" or "Personal interests are still most important"; "Freedom is the ability to be one's own master" or "One's freedom is implemented in one's political rights." The stratification of the sampling was carried out according to standard socio-demographic parameters (gender, age, level of education, type of settlement where the respondent lives, level of material well-being, religious affiliation, occupation), but some additional specifying characteristics of the socio-cultural context were added to these, such as the education of parents and activity of this respondent in the Internet and social networks (daily, 2-3 times a week, once a month, every month).

Without claiming to be exhaustive, we would like to focus here only on what Russians think about the path of Russia's development, what they would want it to be like in the future, and how they perceive their personal and national prospects.

Thinking about the future. As revealed in previous studies, the term "future" has more positive associations in the Russian mentality than does the term "present". In this respect, Russia stands out against other European countries, where "emotional emphases" in the experience of the arrow of time are set somewhat differently [Andreev, 2014: 59]. Thus, in the seemingly overused phrase "Russia is concentrated on the future" one should not see only a tired metaphor, because this concentration is indeed a characteristic feature of our national psychology. In the survey, almost two-thirds of respondents (about 63%) reported that they regularly think about their future, almost a quarter have such thoughts at least from time to time, and just over 5% think about it rarely. Only 6% were completely unconcerned about what is to come. In principle, such a distribution of indicators looks more or less natural. But it is necessary to understand what all these thoughts are caused by and how they are reflected in the internal well-being of an individual. When the future is perceived mainly as frightening uncertainty, or even more so as gloomy hopelessness, or is experienced as a chance, the psychological effect will be quite different. In this connection it is necessary to pay attention to the emotional tone of Russians' reflections on the personal prospects opening up before them. As might be expected, the spectrum of emotions experienced in this case ranges from very bright to extremely gloomy. But oppressive feelings, such as fear and despair, are not very common in this case: they affect up to 8.5% of our fellow citizens, while confidence in favorable prospects, calmness, and hope are experienced in the aggregate by almost 60%. The anxiety widespread among Russians is not in itself an anomaly or a sign of psychological malaise, since anxiety is generally inherent in active life and can be avoided only when one is totally apathetic about everything that is going on.

Russians think not only about their personal prospects, but also about the collective fate of the nation, although less frequently than about their own fate. Only one person out of seven is not interested in such matters at all (Table 1). At the same time, it should be noted that our fellow citizens perceive the future of their country in a much more troubling light than their own future.

Table 1

Do you have to think about your personal future and the future of your country? (as a percentage of respondents, the answer was given for each column)

| Frequency | One had to think | |

| about one's own future | about the country's future | |

| Regularly | 63 | 27 |

| Sometimes | 24 | 35 |

| Rarely | 5 | 19 |

| Didn't think about it | 6 | 15 |

| Found it difficult to answer | 2 | 4 |

Let us say that fear and despair concerning our common future were expressed by approximately 17% of respondents in our survey, and regarding their own future - almost twice as little. On the other hand, approximately 18% feel calm and firmly confident about the future of Russia - this is only one percentage point higher than the percentage of those who are discouraged and despondent.

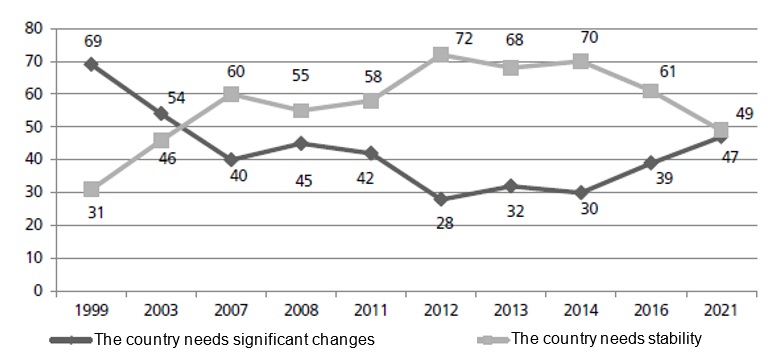

There is a certain weariness of Russians from the accumulated problems; young people in particular do not fully understand the country's development strategy. Obviously, the existing information system is not doing a good job of explaining this strategy, which has led to an increased demand for change. The number of citizens who think that we need new reforms virtually equaled the number of those who would prefer stability to change (47% vs. almost 50%). It should be noted that the proportion of citizens who favor radical changes in Russian society is noticeably lower than in France (68 percent) or the United States (65 percent), although it is higher than in Germany, where it does not exceed the threshold of 39 percent [Wike et al., 2021]. About 10-12 years ago, the gap between the indicators "for change" and "for stability" was much larger: the first of these was approximately at the level of today's Germany (about 40%), while the second reached almost half of the respondents (2008 data). People who identify themselves as supporters of communism, as well as of various versions of socialism, were most often in favor of immediate changes: 59% and 45%, respectively. In the liberal environment, the percentage of those satisfied with the current state of affairs rises to 2/3, and among supporters of an independent Russian path of development - to 70%.

What would Russians want Russia to be like in the future? When asked, our respondents, as in previous years, gave first place to ensuring social justice, which, if we turn to history, has been the main "Russian idea" for centuries. This answer option was supported by more than half of the respondents (the exact figure is 51%). In second place comes the classic set of democratic rights: ensuring individual rights and freedom of expression (41%). They are followed by the preservation of national traditions, time-tested moral and religious values, and strong state authority, with almost equal results (about a third of the answers received). About a quarter of Russians would also like to see their country as a world power - the unifier of peoples. As for such standard elements of the liberal socio-political model as cooperation with the West, private property and free market, minimization of state interference in economy, etc., they, judging by the data we received, appeal to no more than 15-16% of our fellow citizens. The narrowly nationalistic ideal of turning Russia into a "state of Russians" is even less popular; only an eighth of our respondents supported it (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. What would Russians want Russia to be like in the future (in %)

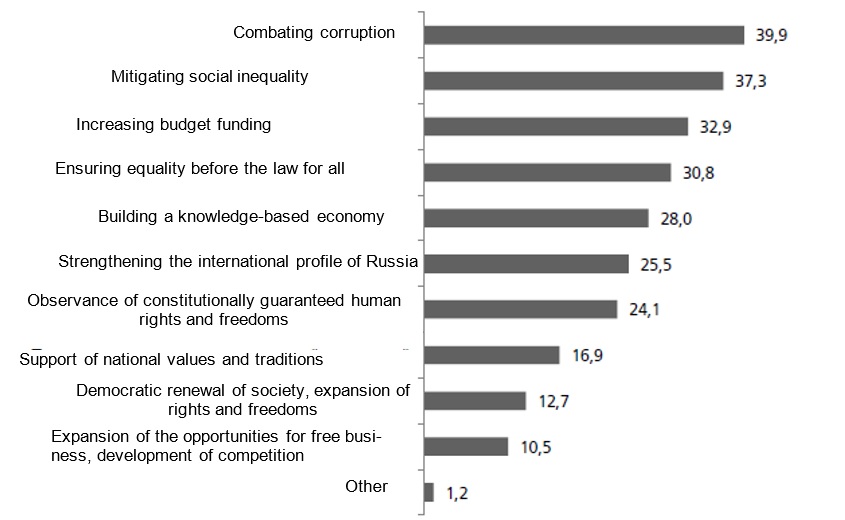

Public opinion has for a long time attached the highest priority to real equality before the law as one of the most urgent tasks that must be resolved in the further development of Russian society. This is the result we have consistently seen in all surveys over the past two decades. According to the spring 2021 data, the highest number of votes (almost 40%) was in favor of a tough fight against corruption. Equality before the law remained among the priorities, but being supported by about 31% of the respondents it moved back to the fourth place, letting mitigation of social inequality (the point of view of 37% of those surveyed) and increase in budget allocations for the social sphere (medicine, education, etc.) take the lead. (However, it is necessary to take into account the opinion of Russians on other aspects of strengthening the rule of law, in particular on the issue of observing the rights guaranteed by the Constitution, which nearly a quarter of our respondents found necessary to mention in their answers as a priority position). Apparently, the acuteness of the problem of ensuring the rule of law was somewhat mitigated by the high-profile arrests of governors, ministers and generals caught on bribes. But it does not cancel the fact that the population is really not satisfied with the organization and financing of health care, and the quality of education and science management is of great concern in the society.

Our fellow citizens also consider the formation of a high-tech economy based on the achievements of modern science and the strengthening of our country's global stature and its effective sovereignty to be important tasks on the way to the future. These points were mentioned by 28 and 25.5% of the respondents in their answers, respectively. However the liberal agenda - the development of democratic institutions, expanding civil rights and freedoms, creating new opportunities for entrepreneurship, ensuring the principle of competitiveness - received rather limited support (in the range of 10-13%) in the context of the country's priorities. Maintaining national traditions and values was also not high on the list of priorities, perhaps because this position is not currently problematic; sufficient attention has already been given to this issue (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Priority tasks that Russia should solve (in %)

The desired image of Russia in the future as seen by its citizens includes a number of elements inherent in modern Western-type societies. At the same time, it also differs in a number of specific ways, and Russians do not share many of the actively propagandized "fundamental" values of the modern West at all. It must be said that our respondents are quite aware of these differences. The majority of them think that Russia should not follow any ready-made models of development and be guided by externally set criteria - it should rely on its own socio-historical experience. This follows from the answers to the questions that presuppose a choice of two alternative value judgments about the path of socio-historical development. In the same or comparable wording such questions were repeatedly included in the program of studies conducted in different years, which gives us an opportunity to consider the views and attitudes of Russian society in historical dynamics. Thus, for two decades we have periodically asked respondents to decide whether Russia should be seen as part of Europe, which should adhere to the same rules as modern Western states, or whether our country is a separate civilization and the Western way of life will never be instilled in it. The year that V.V. Putin was first elected the President of the country, the ratio of supporters of these alternative points of view was 2 : 1 in favor of the pro-European one [Russia on the cusp..., 2000: 406]. More than half of the respondents expressed the opinion that Russia should join the EU as soon as possible. In other words, public mood was largely comparable to what we see, for example, in Georgia, where about 63% of the population rely on support from the United States and the EU [Future of Georgia..., 2021: 24]. However, as the Russian leadership sought to overcome the asymmetry in relations between Russia and the West, and as the West responded with containment strategies and arrogant preachings, ignoring Moscow's concerns and legitimate interests, the vector of Russia's foreign policy orientation began to reverse. In 2007 an approximate parity of two opposing points of view on Russia's fate was recorded: about 35% of respondents agreed with the statement that Russia is part of Europe, the same number joined the opposite thesis - Russia is not a fully European country, it is a special Eurasian civilization, and in the future the center of its policy will shift to the East. It is indicative, however, that in comparison with the previous surveys, the number of those who hesitated and were undecided increased significantly, reaching almost 30% this time. In the 2010s, the outlined tendency continued and the proportion looks again like 1 : 2, only the sides have swapped places: in 2011, the thesis on the European nature of Russia was supported by only 36% of respondents, while about 64% spoke for the fact that Russia is not a European but a Eurasian country.

In 2021, one clarifying addition was made to the set of revealing the theme of Russia's civilizational sovereignty and the uniqueness of the Russian path of development: Russian/Eurasian identity was no longer compared only with Western/European one, but also with Eastern identity: our respondents were additionally offered a choice between judgments: "Russia is a Eurasian power and should cooperate more actively with the countries of the East (China, India, etc.) than with the countries of the West" and "The East is a special world, and we should be very careful with it; it is easier to orient ourselves toward the West, which is more closely tied to us by its culture". In this context, the indicator of support for the Eurasian choice fell slightly to about 53%, while more than 47% of our respondents agreed that it's easier and simpler for us to interact with Europe. One senses that Russia's turn to the East, which has been much talked about in recent years, is perceived somewhat cautiously.

Nevertheless, taking away the "Eastern context" and "leaving Russia alone with the West," we again get the same 1:2 ratio. Thus, according to the results of the choice between the two alternatives: "Russia should live by the same rules as modern Western countries" and "Russia is a separate civilization, the Western way of life will never be instilled in it" - the first was supported by slightly more than one third of the respondents (more precisely, 35%) and the second by almost twice as many (65%). Only young people under 25 years of age fall out of the picture: three out of every five respondents in this group hold pro-Western views. However, the two-fold prevalence of the supporters of the Russian distinctness is almost restored in the next age cohort (26-35 years old), and after 55 years old it becomes at least three-fold. By the way, an orientation to the Western way of life and Western models of development in the eyes of young people does not yet mean "friendship" or even active partnership with the West, let alone any geopolitical obligations to it, including assistance in strengthening the so-called "common European home". Over 76% of our youngest respondents (up to 26 years of age) were against this formulation of the question. This number is certainly lower than in older age groups, where the value of this indicator exceeded 85% (in the 45-55 age cohort) and even 90% (respondents over 55), but it is nevertheless quite eloquent. Besides the point, the distinction between sympathies for Western life and Russia's geopolitical interests fundamentally distinguishes the attitudes of today's youth from the exalted Westernism characteristic of the middle-class urban Russians in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The Russian understanding of democracy. Closely connected to the Russians' choice of civilization is the thorny question of democracy, which in recent years has become almost the main point of Western criticism towards Russia. Although, as has already been noted, Russians for the most part refuse to accept the Western model of development as an immutable model, it does not follow that they reject the idea of democracy as such. Moreover, of those elements and features of social structure which are considered characteristic of Western societies and which Russians also consider appropriate for themselves, almost all are precisely the various characteristics of democracy. About 2/3 of our respondents said that Russia should be a democratic state, where human rights and individual freedom of expression are guaranteed. Those who believe that democracy will not be instilled in us and that we need a strong individual power capable of ensuring order and unity of the country were in the minority (although their number is statistically significant).

Let us consider another issue, which concerns political freedoms, elective authorities and fair elections, the right to express one's opinion, including through meetings and demonstrations. Almost 3/4 of our respondents agree with the fact that all these things must exist in Russia, and only slightly more than a quarter of them think that these rights should be restricted in order to maintain stability and order.

At the same time, describing Russians' ideas about what Russia should be like, we emphasize that our society has formed its own vision of democracy, which differs from its normative understanding in the West. For example, the majority of our citizens are not inclined to associate freedom with political rights. Freedom in the Russian interpretation is somewhat apolitical - it is rather the absence of restrictions or at least their minimization - what we call the volya (it is no coincidence that more than half of our respondents spoke out against monitoring the movement of people within the country, if the aggravation of the coronavirus situation requires it). Another illustrative example: the majority of Russian citizens recognize the legitimacy and necessity of the existence of a political opposition (a normative element of democracy, which is of great importance in the West), but are not inclined to consider it in the context of the "political pendulum" model characteristic of Western democracies (regular change of political leaders and political parties in power). Gender equality, which has lately been recognized in the West as the most important criterion of democracy, also enjoys considerably less support in Russia: 54 percent versus 90-96 percent in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, Sweden, Australia, or at least 62-70 percent in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Israel [Pew..., 2021]. In general, Russians are characterized by a desire to combine democratic ideals with the historical experience of the political organization of the Eurasian space, which suggests the need for a strong centralized state. The commitment to this model of statehood or, on the contrary, to the decentralization and delegation of more and more power to the localities that is encouraged in Europe divides contemporary Russian society virtually in half: in our survey 52 percent of respondents favored the first alternative, while 48 percent favored the second.

Ideas capable of uniting Russians. But if the state is not so much a mechanism for coordinating interests as a kind of integrator of the national will, this immediately raises the question of a unifying idea (or ideas) under which the Russia of the future will be built. The data at our disposal allow us to consider this question in dynamics as well. The main ideas which, as Russians believe, can unite the Russian society, have been defined long ago. These are the unity of the peoples of our country for the purpose of its revival as a great power, the strengthening of Russia as a democratic and law-governed state, and the unification of peoples in the name of the solution of global problems of mankind. Since this question was first proposed to our respondents (1995), the composition of these three ideas and their distribution by the level of importance (it was determined by the number of respondents who named one or another idea) has remained practically constant. In 1995, 41.4% of those surveyed chose the idea of reviving Russia as a great power as a priority; in 2001, 48%; in 2011, 42% and in 2021, 40%. In 1995, 30% "voted" for the idea of strengthening the Russian Federation as a democratic and law-governed state; in 2001 - 48%; in 2011 - 38%, in 2021 - 30% again. In favor of unification of peoples for the sake of solving global problems of mankind in the same years 23.5%, 24%, 26% and 25% pronounced themselves respectively. As we can see, these figures have varied very little over the course of a quarter of a century. More significant changes took place in the middle and lower parts of the list, where less popular, but still widespread variants of the national idea are listed. For example, a return to socialist values in 1995 was supported by only 10% of respondents; in 2011 - twice as much, in 2021 - over 22%. It is hardly necessary to explain specially what shifts of public mood are hidden behind these dynamics. The idea of confrontation with the West was rising in a similar way: in 1995 it was appealing to only 2% of respondents, and by 2021 this proportion increased more than fourfold. Almost the same number (about 10%) of respondents holding an opposite standpoint and advocating embrace of the West and joining the common European house (in 1995 it was over 12%, and this number exceeded the number of supporters of embrace of the West almost six-fold) turned out to be in our sample. The number of Russians who believe that our society could be united by the belief in a special historical mission of the Russian people has somewhat increased for a quarter of a century. In 1995, they accounted for 7% of our sample; in 2011 - 9%, and in 2021 - about 11%. On the other hand, judging by the data we received, the "social weight" of the fixation on the purification of society through the Orthodox faith decreased a little: if in the 1990s it gathered 5-6% of votes, then today only 4%. Among the possible options for a national idea, the survey suggested such options as the unification of the Slavic peoples, the broad autonomy of the regions within the Russian Federation, and the priority of the interests of the individual over the interests of the state. Some of these ideas themselves find a certain resonance among Russians, but even the majority of their supporters do not consider them to be a unifying or rallying idea. Thus, in contrast to the value orientations of Soviet times, a large part of the population today puts personal interests above public and state interests, their share reaches 2/3. Nevertheless, there are many times fewer supporters of bringing state and public interests down from the ideological pedestal as an ideological basis for the consolidation of Russian society. In 2011 there were about 8% of them; by now this number has slightly increased - up to 12%, which, however, does not change the overall picture much. The ideology of individualism, despite its prevalence, has still not gained mass recognition in our country. Under the column "Another Idea" some of our respondents inscribed the resignation of V. V. Putin from the post as the President of the Russian Federation. We have found 0.4% of such in our sample.

Assessment of the Current Path of Development of the Country. When asked whether Russia is following the right path today and whether it will lead to positive results, more than half of the respondents (55%), despite all the difficulties experienced recently (Western sanctions, COVID-19, high levels of corruption, etc.), answered in the affirmative. At the same time, it is noteworthy that the value of this indicator, which had been rising steadily for a long time after 2000, has declined by more than 20 p.p. over the past 5-6 years (Table 2). Nevertheless, 55% is 8 percentage points higher than the above-mentioned value of the indicator characterizing the intensity of the demand for changes forming in the society (47%). Hence it can be concluded, at least presumably, that the need for change has been at least partially satisfied, and this, in turn, leads Russians to the idea that the current government, for all its shortcomings, is basically coping with the country's development tasks (Fig. 3).

Table 2

Opinions on Russia's Path of Development, 2001-2021 (as a percentage of the number of respondents)

| Statement | 2001 | 2011 | 2014 | 2016 | 2021 |

| The path Russia is following will yield positive results in the long term The path Russia is following leads to a dead end | 59 | 60 | 76 | 65 | 55 |

| 39 | 39 | 24 | 35 | 45 |

Fig. 3. Dynamics of People's Assessment of the Necessary Changes in Russia (in %)

Demand for Change and Ideological and Political Segmentation of Society. The variety of opinions on various aspects of Russia's future development that we have described here is all integrated into the four consolidated ideological movements that have emerged in contemporary Russian society, which can be characterized as right- and left-wing liberal, social-traditionalist (left of various trends, including both orthodox and unorthodox communists), and conservative-statist (the core of which consists of supporters of a Russian independent development path focused on one or another version of "national" state capitalism ). However, the process of ideological self-identification and party segmentation of Russian society is complicated to a certain extent: only a third of our respondents could give a definite answer to the question concerning their affiliation with any particular ideological movement. Approximately 7% ascribed themselves to liberals and advocates of a market economy, approximately 18% as left (including nearly 11% - as communists), and almost 7% as supporters of an independent national path of development. Most respondents could not definitely answer the question about their ideological choice: almost every second respondent said they did not support any movement, while about 18% said they supported a combination of various ideas, avoiding extremes at the same time. In total, this "sector of uncertainty" amounts to more than two-thirds of our sample.

In a situation of "recurring ideological changes," it is difficult for citizens to choose a party that would sufficiently correspond to their ideas about how the country should be run. A considerable part of the Russian electorate feels uncertain about the choice that is to be made, and cannot make up their mind until the very moment of voting. In particular, in the spring of 2021, five months before the elections, only 44% of our respondents confessed that they would not vote for any party, that they would not go to the elections, or that they could not yet decide whom they should support this time.

In this connection it would be natural to raise the question about the length of the life cycle and the "wearout period" of various political projects. After all, even in contemporary clip way of thinking, sooner or later the problem of verification arises. In the specific psychic atmosphere of the postmodern, this or that party or movement can, of course, simultaneously hand out advances to liberals, supporters of a "strong" state, and socialists, as well as to modernization enthusiasts and traditionalists. But advances always involve expectations that must someday be met, at least in part. And in politics, this "someday" usually fits into fairly close time horizons and may even mean something like "in the next electoral cycle.

We cannot delve further into this rather special and difficult topic here. However, we cannot help mentioning some specific symptoms, foreshadowing the occurrence of similar problems in the future. Let us take for comparison the dynamics of the segmentation of the electorate of the "United Russia" according to its political preferences on the threshold of the previous and forthcoming parliamentary elections in September of this year. In the first case, the forecast estimates, based on the data of sociological monitoring of the elective field, already six months before the elections (March-April 2016) proved to be very close to the actual voting results. For example, the VCIOM (All-Russian Public Opinion Research Center) April forecast for United Russia was 47-48% of the vote, while the actual result was just over 54% in the nationwide constituency and about 48% in the single mandate constituencies. The projected estimates for the other parties that participated in the elections were also close to the actual election results. In 2021, however, the picture looks different. The survey we conducted gave UR (United Russia) only a little more than 17% of voters who had already made up their minds. The forecast of the VCIOM April survey is more optimistic - about 29% [Ratings of confidence in politicians..., 2021]. However, it is also far from the 47-48% that sociologists promised the government party six months before the 2016 elections. Forecasts for other political actors are still close to the results they usually get in elections. However, we should pay attention to the fact that the increase in doubts in relation to the government party is not accompanied by a proportional increase in the influence of any other political actor, as usually happens in the framework of the "pendulum" model of elective democracy. And this, in our opinion, can be seen as a symptom of increased uncertainty and increased doubts of Russians in general. We can also talk about the crisis of the institution of political parties as the spokespersons of the interests of the population. In fact, parties have the lowest confidence rating of all political and public institutions in the country: according to sociological surveys, only one out of five citizens trusts them.

Nevertheless, a significant majority of the population (over 63%) believes that despite all the shortcomings of the current government it still deserves support. This is noticeably higher than the 47% who preferred stability to change. Another question is that in mass consciousness authorities are identified not so much with some formal "government institutions", as with a complex system of multilevel relations of state institutions, public organizations, "think tanks" and generators of information flows, the uniting center of which is the figure of the President. A simple calculation shows that at least one third of our respondents, who support the idea of the necessity in changes, vote "for the authorities". Probably, it should be understood in such a way that the majority of the population relies upon the present leadership of the country for their implementation.

References

- 1. Andreev A.L. (2014) Russians and Europeans: Cultural and Psychological Characteristics of People and Soci-eties. In: Russia and Europe. Vol. 1: History, Traditions and Modernity. Moscow: Veche: 50–100. (In Russ.)

- 2. Confidence Rating of Politicians, Assessments of the Work of the President and the Government, Support for

- 3. Political Parties. (2021) WCIOM. April 9. URL: https://old.wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=10747 (ac-cessed 02.05.2021). (In Russ.)

- 4. Future of Georgia: Survey Report. (2021) CRRC Georgia. URL: https://crrc.ge/uploads/tinymce/documents/Future%20of%20Georgia/Final%20FoG_Eng_08_04_2021.pdf (accessed 02.05.2021).

- 5. Mass Information in the Soviet Industrial City. Moscow: Politizdat. (In Russ.)

- 6. Russia at the Turn of the Century. (2000) Moscow: ROSSPEN. (In Russ.)

- 7. Wike R., Silver L., Schumacher S. (2021) Many in US, Western Europe Say Their Western Europe Say Their Political System Needs Major Reform. Pew Research Centre. March 31. URL: https://www. pewre-search.org/global/2021/03/31/many-in-us-western-europe-say-their-political-system-needs-major-reform/ (accessed 02.05.2021).