- Код статьи

- S013216250016782-3-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S013216250016782-3

- Тип публикации

- Статья

- Статус публикации

- Опубликовано

- Авторы

- Том/ Выпуск

- Том / Номер 9

- Страницы

- 175-188

- Аннотация

The disintegration of the USSR was a natural consequence of the Soviet national policy aimed at accelerating the modernization of the Union republics and equalizing their levels of development. By launching the process of the de-Russification (‘korenizatsiya’) of managerial personnel, Moscow has contributed to the formation of modern national elites on the ground. The implementation of the national-state construction project led to the nationalization of ethnic and interethnic relations and the sovereignization of the Union republics, а key factor in the collapse of the USSR.

- Ключевые слова

- disintegration of the Soviet Union, national policy, ‘korenization’ policy, ethnic structure of the state apparatus, ethnic discrimination, de-Russification of the government bodies

- Дата публикации

- 27.09.2021

- Год выхода

- 2021

- Всего подписок

- 6

- Всего просмотров

- 319

Researchers have studied the circumstances and causes of the collapse of the USSR with unflagging interest for thirty years. According to estimates, more than 3,000 articles, 300 books and 20 dissertations had been completed in the Russian Federation alone by the beginning of September 2020. One can divide the explanations for this disintegration into two groups: the first considers the disintegration to be the natural consequence of processes developing over time, the second views it as the result of a combination of random circumstances, management errors and external factors. The first group often refers to the disintegration as a breakup, implying the regularity of the process and the result; the second designates it a collapse, suggesting the randomness of the phenomenon and its results [Mironov, 2021].

The disintegration of the USSR is assessed in the historiography as a geopolitical catastrophe on a global scale. To understand its causes, it is necessary to analyze many factors in an interdisciplinary framework, relying primarily on statistical sources. Such research can be performed by a research team. An individual researcher can address limited tasks. This article attempts to consider the disintegration of the Soviet Union from the perspective of discrimination against ethnic groups, especially the titular ethnic groups of the union republics, which in the constitutions of 1924 and 1936 possessed limited, or potential, state sovereignty, and in the constitutions of 1977 and 1990, full sovereignty. The titular ethnos is the nation whose name a republic bears; there were fifteen such nations from 1956. Such a perspective has been selected on the one hand because of the importance of the problem, for political inequality took a prominent place both in the programs of national parties and movements during “perestroika” and in explanations of the disintegration in ethnopolitical studies. On the other hand, there are mass statistical sources that make it possible to measure the extent and dynamics of ethnopolitical inequality in the Soviet period by the degree of the presence of representatives of different nations in state administration, parliament, the police and the courts, as well as in the army from 1897 to 1989. Russian ethnosociologists have long studied the problem of ethnic conflict arising from the inequality of the ethnosocial and ethnopolitical statuses of the peoples in Russia [Harutyunyan, Drobizheva, 2016: 29-38]. The research of a team of sociologists within the framework of three large international projects led by L. M. Drobizheva became a landmark on this path [Asimetric Federation..., 1998; Democratization..., 1996; Conflict ethnicity..., 1995; Social and cultural distances..., 2002; Social inequality..., 2002; Sovereignty..., 1995; Values and symbols..., 1994; etc.]1. These ethnosociologists reached conclusions explaining interethnic conflicts in Soviet and post-Soviet Russia. In particular, they consider the political sphere as the main space in which Russians and non-Russians perceive their inequality. Discrimination in access to power is the most important cause of interethnic conflict. Ethnic groups consider the possibility of and actual participation in administration as the criterion for assessing their position in society and as an indicator of discrimination. The strengthening of democracy in the formation of government bodies solves some problems but raises other issues. Modernization gives contradictory results. Education, personal freedom, a prestigious profession, prosperity, free time, and access to all benefits generate new needs for ethnic groups, especially for those lagging in economic and cultural terms, new demands that previously were absent. The real capabilities of a society and a state to meet these needs, however, do not keep pace with their growth; the existing principles of distribution of benefits do not seem fair to everyone. Relative deprivation arises, provoking personal discontent. When a state machine weakens and a government is perceived as illegitimate, discontent is transformed into conflict and open insubordination, as happened in Russia in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The main subject of this paper is the political inequality of the peoples in the Soviet Union as the cause of its collapse. The object of this research is the apparatus of administrative and security agencies personnel in the union republics and the USSR as a whole. There are two specific tasks: 1) to measure the level of discrimination in the formation of the power structures; 2) to determine the participation of titular ethnic groups in the governance of the USSR and the union republics.

The role of various ethnic peoples in public administration is determined not only by the number of their representatives in power; also important is what command positions they occupy, how effectively they use them, and what personal status, prestige and influence they have. Nevertheless, participation in governance is of paramount importance, as evidenced by the (usually informal) mechanism of parity and proportional quotas based on ethnicity in the system of state authorities, which was applied in the multiethnic union and autonomous republics of the USSR and is currently found in autonomous regions of the Russian Federation. This technology is used because the democratic principle of staffing government entities in conditions of free competition does not always ensure the proportional representation of ethnic groups, which seems unfair to the latter, although ethnic quotas guarantee neither the professionalism of officials, nor their responsibility, conscientiousness or morality, and often gives rise to nepotism. The mechanism of quotas was especially important in the Central Asian, Caucasian and North Caucasian union and autonomous republics, in which remnants of clan relations and community orders and traditions have persisted, and kinship and local relations have played an important role in society [Informal ethnic quotas..., 2017: 1-53; Fedorchenko, 2010: 692-705].

The ethnic structure of the Soviet and Communist Party apparatus has long attracted the attention of researchers. The party’s historians dealt with this subject in the Soviet period; and historians, sociologists and political scientists have done so in post-Soviet historiography, not specifically but in the context of the cultural, social and demographic profile of Soviet and party functionaries. This research has revealed much information. The data is chronologically and geographically fragmentary, however, which does not allow one to obtain a general picture of the ethnic composition of government bodies over the years of Soviet rule. The present research addresses this challenge for the first time in the historiography, as far as I know, on the basis of all-union population census data, which, although utilized by my predecessors, was also employed in a fragmentary fashion (see, for example, Dynamics..., 2002; Social inequality..., 2002). While the data on ethnic employment according to the 1926 census had been published, it was not summarized for the USSR and the RSFSR [All-Union Census..., 1928-1930], and the data from subsequent censuses has been stored in the archives [All-Union census..., 1959; All-Union Census..., 1979; All-Union Census..., 1989]. The census of 1897 [General Code..., 1905] has records of officials of imperial and municipal bodies without division by rank, class and character of occupation. The Soviet censuses in the sphere of state administration counted only the leadership of the executive and legislative authorities, the Communist Party and public organizations, but with respect to the courts and police the censuses contain data about all their professional employees . A comparison of the data of the CSO statistics and the censuses found that senior employees constituted 31% of all administrative personnel in 1926, 21% in 1959 and 1970, and 26% in 1979, that is, one manager supervised three orfour ordinary officials. The Soviet census data on the number of persons employed in administration are not comparable with the data of 1897; but they are comparable with each other, since the criteria for classifying persons as managers were identical—the leaders of the party, executive and legislative authorities were included in the state administration. One cannot identify rank-and-file officials as a separate category in the census materials. Rank-and-file officials/Ordinary officials were not singled out into a distinct professional group, imperceptibly dissolving in the general mass of employees, and it is impossible to identify them in the census materials.

To determine the degree of equality in the staffing of state bodies I use ethnopolitical representativeness (hereinafter IEPR), the ratio of the percentage of representatives of an ethnic group to the total number of administrative officials and to the entire employed population [Mironov 2017: 197-210; Russians..., 1992]. In the literature this indicator is also known as the index of ethnic discrimination, the index of participation, and in English-language studies the index of representativeness (ethnic representation proportionality index). This indicator allows one to assess the degree of political inequality and to rank the ethnic groups accordingly. If this index is greater than or less than 1, then the ethnic group is excessively or insufficiently represented in the power structures. If this is equal to 1, the rights of this ethnic group are adequately considered when forming governing bodies. Another operational indicator measures the participation of various ethnic groups in governance—the percentage of those who were promoted to higher-level positions (vydvizhentsy) in the Soviet state and the Communist Party, police and judicial structures.

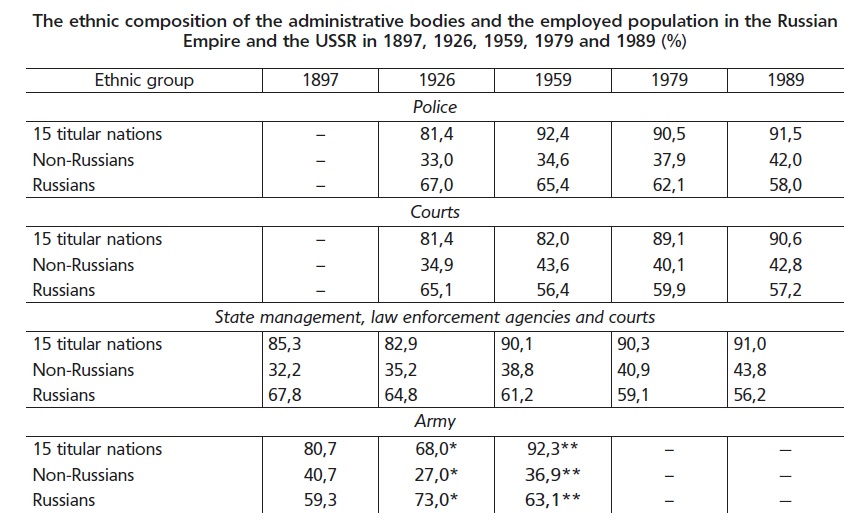

Let us evaluate the dynamics of ethnopolitical representativeness in the country as a whole. The scope of the article makes possible the provision of mainly relative data and summary information about Russians and non-Russians (Table 1). In 1897, non-Russian peoples participated in the staffing of the power structures at a ratio 1.6 times lower than the democratic norm (1.00 : 0.61 = 1.6) and 2.3 times lower than that of Russians (1.43 : 0.61 = 2.3). There is no doubt that this constitutes ethnopolitical inequality. At the same time, let us note that non-Russian citizens had representatives in government bodies. The IEPR of non-Russians increased in all government structures from 0.61 to 0.79 by 1926, and their representation became only 1.3 times lower than the democratic norm. Subsequently, this upward trend gained strength; by 1989 the inequality was minimized: the IEPR of non-Russians was 0.93 and of Russians 1.06. Russians had lost their former privileges. In different spheres of government ethnic inequality had been eliminated at different rates. Equality had become a fact in the state apparatus as early as in 1959. In the apparatus of the public and party organizations, the IEPR of Russians slightly exceeded the democratic norm (1.05) even in 1989. The police and courts both before and after 1917 employed non-Russians as personnel to a lesser extent than Russians, but even here the inequality decreased. In judicial institutions non-Russians had an IEPR of 0.78 in 1926 and 0.91 in 1989, and the index for Russians was 1.17 and 1.08, respectively. The IEPR of non-Russians in the police was 0.74 in 1926 and 0.90 in 1989, while the IEPR of Russians was respectively 1.21 and 1.09. The IEPR of non-Russians in the armed forces was 0.77 in 1897 and 0.67 in 1926, and that of Russians was 1.25 and 2.79, respectively. Information about the ethnic composition of the army became classified after 1926. It can be assumed from fragmentary data that subsequently the share of Russians in the army remained higher than their share in the population of the USSR.

Tab. 1 Representation of non-Russians and Russians in the governing bodies of the Russian Empire* and the USSR in 1897, 1926, 1959, 1979 and 1989

| Ethnic Group | 1897 | 1926 | 1959 | 1979 | 1989 |

| Non-Russians | – | 0,81a | 1,00 | 0,99 | 1,00 |

| Russians | – | 1,15a | 1,00 | 1,01 | 1,00 |

| 15 titular nations | – | 1,02a | 0,99 | 1,00 | 1,00 |

| Non-Russians | 0,62b | 0,81 | 0,79 | 0,91 | 0,94 |

| Russians | 1,42b | 1,15 | 1,18 | 1,07 | 1,05 |

| 15 titular nations | 1,10b | 1,02 | 1,03 | 1,02 | 1,01 |

| Non-Russians | – | 0,78 | 0,94 | 0,89 | 0,91 |

| Russians | – | 1,17 | 1,05 | 1,09 | 1,08 |

| 15 titular nations | – | 1,01 | 0,93 | 0,99 | 1,01 |

| Non-Russians | – | 0,74 | 0,74 | 0,84 | 0,90 |

| Russians | – | 1,21 | 1,22 | 1,13 | 1,09 |

| 15 titular nations | – | 1,06 | 1,05 | 1,01 | 1,01 |

| Non-Russians | 0,61 | 0,79 | 0,84 | 0,91 | 0,93 |

| Russians | 1,43 | 1,17 | 1,14 | 1,07 | 1,06 |

| 15 titular nations | 1,09 | 1,03 | 1,02 | 1,01 | 1,01 |

| Non-Russians | 0,77 | 0,67c | 0,89d | – | – |

| Russians | 1,25 | 2,79c | 1,09d | – | – |

| 15 titular nations | 1,04 | 0,80c | 1,04d | – | – |

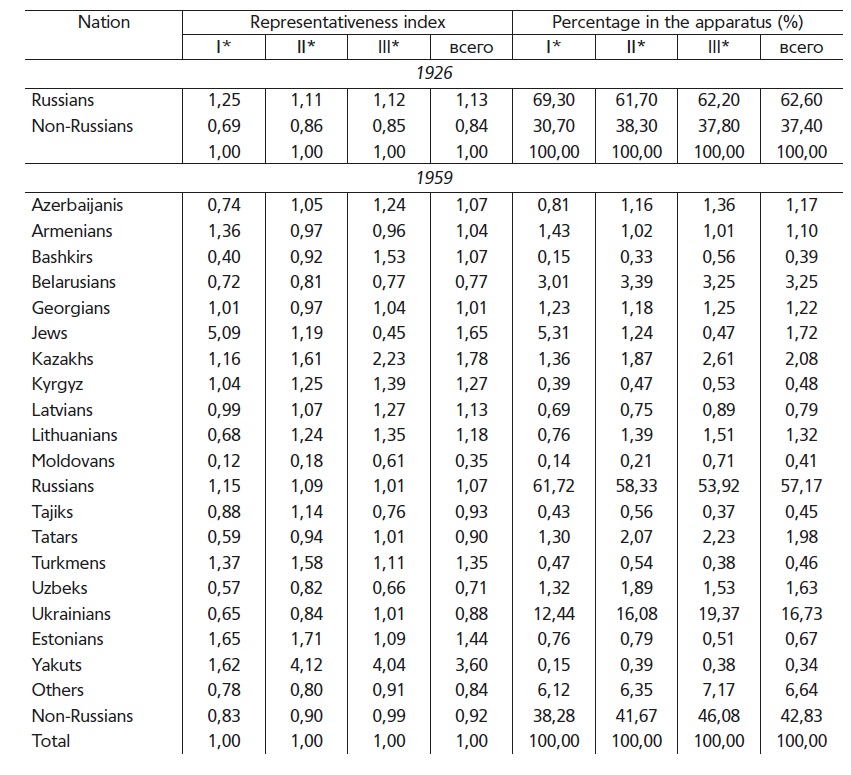

The degree of representativeness of non-Russians and Russians was different at different levels of power. Russians were prevalent in the state administration in 1926, but to a greater extent at its highest level: The IEPR of Russians at the lowest levels was 1.14, at the middle level 1.15, and at the highest levels 1.27, and of non-Russians 0.83, 0.81 and 0.66, respectively. Ethnic inequality among state officials had significantly decreased by 1959; at the middle and lower levels of governance it had disappeared (Table 2).

Tab. 2 The representativeness of non-Russians and Russians in different spheres of state management in the USSR in 1926, 1959, 1989

| Level of administration | Russians | Non-Russians | ||||

| 1926 | 1959 | 1989 | 1926 | 1959 | 1989 | |

| State apparatus | 1,15* | 1,00 | 1,00 | 0,81 | 1,00 | 1,00 |

| Heads of all-union, republican, regional and district bodies | 1,27 | 1,14 | – | 0,66 | 0,84 | – |

| Heads of district and city bodies | 1,15 | 1,06 | – | 0,81 | 1,04 | – |

| Heads of local Communist organizations | 1,14 | 1,00 | – | 0,83 | 1,00 | – |

| Apparatus of the Communist Party | 1,15* | 1,18 | 1,05 | – | 0,79 | 0,94 |

| Heads of structures of Union, Republic, regional and local levels | 1,27 | 1,17 | – | – | 0,80 | – |

| Heads of local and city structures | 1,15 | 1,11 | – | – | 0,88 | – |

| of local Communist organizations | 1,14 | 1,27 | – | – | 0,69 | – |

| State and Communist Party apparatus, courts and police? | 1,17 | 1,07 | 1,06 | 0,79 | 0,84 | 0,93 |

Note. *For 1926 г. the apparatus of state, party and public organizations is merged for the accounting of personnel.

Within the Communist Party structures, according to data for 1959 (there is no comparable information for other dates), the situation was different. Russians had an advantage at all levels: the IEPR of Russians on the lower rungs was 1.27, on the upper rungs 1.17, and of non-Russians 0.69 and 0.80, respectively. By the end of the Soviet period ethnic inequality within the governing structures had significantly decreased and had disappeared among state officials. In the party apparatus, at the highest level of executive power and in the security agencies, however, the representation of Russians was slightly higher than their share in the population.

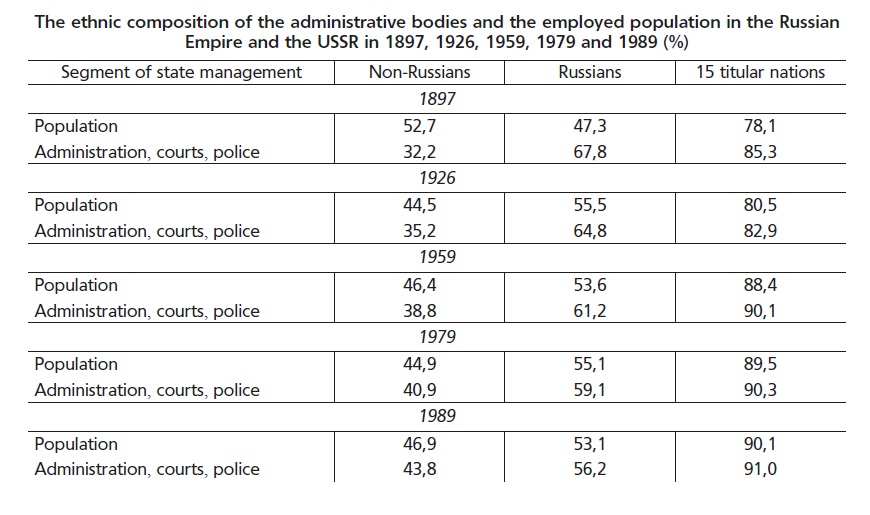

Let us now consider the data on the participation of individual ethnic groups in governance. The percentage of non-Russians among officials gradually increased: it was 32.2% in 1897, 35.2% in 1926, and 43.8% in 1989. In 1987 Russians were numerically represented in the power structures as a whole at a percentage slightly higher than their share in the country's population (Table 3). From 1959 to 1979, the number of officials in the state apparatus increased by 1.1 times; the number of persons in the Communist Party apparatus had risen by 2.5 times, and the percentage of all those employed who worked in the party apparatus increased from 37% to 56%, respectively. The Communist Party leadership began to prevail over Soviet officials not only in their degree of power but also in quantity. This trend also continued during the years of perestroika: the Communist Party apparatus decreased by 17.5% and the Soviet apparatus by 86.3%; the imbalance in favor of the former increased [National Economy..., 1990: 50].

Tab. 3

The ethnic composition of the administrative bodies and the employed population in the Russian Empire and the USSR in 1897, 1926, 1959, 1979 and 1989 (%)

Let us now gauge the participation of different ethnic groups in various power structures.

Tab. 4 The ethnic composition of the administrative bodies and the employed population in the Russian Empire and the USSR in 1897, 1926, 1959, 1979 and 1989 (%)

Non-Russians participated in state administration in 1897, although their share was two times less than that of Russians, 32.2% versus 67.8%. The percentage of non-Russians within all government bodies increased to 35.2% by 1926, to 38.8% in 1959, and to 43.8% in 1989. The participation of non-Russians also grew in the security forces, but until the end of the Soviet regime they were underrepresented in their work.

The Center always relied on local elites in the nationalities policy of the Russian Empire [Mironov, 2017: 378], but the Center never set the goal of nationalizing interethnic relations, granting state sovereignty to the peoples of the "national borderlands"; St. Petersburg was well aware of the danger of such a policy for the unity of the country. Soviet Moscow began to consistently follow the democratic principle of personnel recruitment from indigenous ethnic groups for administrative organs. Consequently, the share of non-Russians in the administration as a whole throughout the USSR grew but remained below 50% as a rule, because up to 1991 the percentage of Russians in the population of the Soviet Union was more than half (Russians constituted 50.8% of the total population and 53.1% of the employed population in 1989). This gave the Russians slight numerical superiority in the administrative hierarchy. It should be emphasized that ethno-political status increased among all non-Russian ethnic groups, not only among the titular ethnicities. The share of non-Russians in government bodies was 32.2% in 1897, 52.7% in the employed population, and the IEPR stood at 0.68; in 1926 these figures were 36.5%, 47.9% and 0.76, respectively; in 1959 these indicators were 38.7%, 46.4% and 0.83, respectively; in 1979—41.2%, 47.6% and 0.87, respectively, and in 1989 they reached 48.7%, 49.2% and 0.99, respectively. By 1989 non-Russians were represented in government bodies at a ratio close to the democratic norm and occupied about half of the leadership positions (Table 1).

Tab. 5

The ethnic composition of the administrative bodies and the employed population in the Russian Empire and the USSR in 1897, 1926, 1959, 1979 and 1989 ( %)

| Nation | 1897 | 1959 | 1979 | 1989 | 1897 | 1959 | 1979 | 1989 |

| State management | Population | |||||||

| Azerbaijanis | – | 1,0 | 1,7 | 2,1 | – | 1,1 | 1,6 | 2,0 |

| Armenians | 0,8 | 1,0 | 1,7 | 1,5 | 1,6 | 1,1 | 1,5 | 1,4 |

| Bashkirs | 0,1 | 0,3 | 0,5 | – | 0,5 | 0,4 | 0,5 | – |

| Belarusians | 2,3 | 3,4 | 3,2 | 3,7 | 3,6 | 4,2 | 3,8 | 3,8 |

| Georgians | 0,9 | 1,2 | 1,1 | 2,0 | 1,4 | 1,2 | 1,3 | 1,4 |

| Jews | 0,8 | 1,6 | 0,8 | – | 0,7 | 1,0 | 0,6 | – |

| Kazakhs | 1,3 | 1,6 | 2,6 | 3,1 | 2,5 | 1,2 | 1,8 | 2,4 |

| Kyrgyz | – | 0,3 | 0,5 | 0,6 | 0,7 | 0,4 | 0,5 | 0,7 |

| Latvians | 1,1 | 0,6 | 0,6 | 0,6 | 0,5 | 0,7 | 0,5 | 0,5 |

| Lithuanians | 0,8 | 0,9 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 1,1 | 1,1 | 1,0 | 1,1 |

| Moldovans | 0,3 | 0,3 | 0,6 | 0,8 | 1,1 | 1,2 | 1,1 | 1,2 |

| Germans | 1,7 | – | – | – | 0,7 | 0,8 | 0,7 | – |

| Russians | 67,8 | 61,2 | 59,1 | 56,2 | 47,3 | 53,6 | 55,1 | 53,1 |

| Tajiks | 0,0 | 0,4 | 0,7 | 0,7 | 1,1 | 0,5 | 0,8 | 1,0 |

| Tatars | 1,4 | 2,2 | 2,3 | – | 2,4 | 2,4 | 2,5 | – |

| Turkmens | 0,0 | 0,3 | 0,4 | 0,6 | 0,8 | 0,3 | 0,5 | 0,7 |

| Uzbeks | 0,0 | 1,6 | 2,5 | 2,7 | 4,8 | 2,3 | 3,4 | 4,4 |

| Ukrainians | 9,3 | 15,4 | 14,1 | 15,0 | 16,2 | 19,1 | 16,4 | 16,0 |

| Estonians | 0,8 | 0,5 | 0,4 | 0,4 | 0,4 | 0,5 | 0,4 | 0,4 |

| Yakuts | – | 0,2 | 0,3 | – | 0,1 | 0,1 | 0,1 | – |

| Non-Russians | 32,2 | 38,8 | 40,9 | 43,8 | 52,7 | 46,4 | 44,9 | 49,9 |

All non-Russians experienced an increase in their political status in Russia (Table 5). Most of them participated in ruling the "prison of the peoples", as historians of the former union republics and some autonomous republics now call the Russian Empire [Mironov, 2017: 121-139]. Ninety-seven nations out of the 118 included in the 1897 census had at least one representative in the governing bodies. Among them were Aleuts, Giliaks, Kamchadals, Tunguses, Gypsies, Eskimos, Yakuts and others. Seventy-nine nations had more than 10 representatives, 55 nations had more than 100 representatives, and 22 nations had more than 1000. Also participating in the governing bodies were 2587 Jews, including 7% outside the pale of settlement [General Code..., 1905: 335]. Among officials, the percentage of non-Russians (mainly in local government structures) was significant—32.2%. In the "national borderlands" (within the borders of the Soviet Union, excluding the Russian Federation), non-Russians prevailed numerically in administration—they constituted 56.5% of all officials. This clearly proves that in the "national borderlands" the central government relied on local elites. In the Soviet era, their presence in government bodies increased even more, and by 1979 their representativeness approached the democratic norm. Moreover, those promoted from non-Russian ethnic groups (vydvizhentsy) were employed at all levels of power (information about this is available only in the censuses of 1926 and 1959) (Table 6).

Tab. 6

The national composition of the state and party apparatus of the USSR in 1926 and 1959 at different levels

Note. *I – All-union, republic-level, and regional (oblast') organs; II –district (raion) and city organs; III – heads of local organizations. The Russian Empire [Mironov, 2017: 152-163].

For example, in 1959 the share of Jews in the state and party apparatus was 1.72% (including in the highest echelon—5.31%). Jews’ share among the population was 1.04% in that year. They were represented in the state and the Communist Party apparatus at a ratio 1.65 times higher, and at the highest echelon 5 times higher, than the democratic norm (their IEPR was 1.65 and 5.09, respectively). The participation of non-Russians in the power structures in the Union as a whole increased and accelerated in the years 1897–1989, while in contrast such participation by Russians decreased. In the years 1897–1926, a period of 29 years, the share of Russians fell by 3 percentage points; in the period 1926–1959, a span of 33 years, by 3.6 points; and in the years 1959–1989, a period of 30 years, by 8.1 points. It is a mistake to think that during the period 1897–1926 the entire increase in the share of non-Russians in government bodies occurred in the first post-revolutionary decade. The involvement of local elites in the ruling structures was always a principle of the nationalities policy of the Russian imperial government.

The so-called policy of indigenization (korenizatsiia) (the creation of autonomous regions, the promotion of representatives of local elites to the leadership, the use of national languages in recordkeeping and education, and the development of mass media in the indigenous languages) [Martin, 2011], which began in the 1920s, not only continued the policy of St. Petersburg, but raised it to a new level, the level of sovereignization, setting the goal of creating essentially sovereign states from the union republics. The policy of indigenization in some respects ended in the 1930s, but the sovereignization of the republics largely continued until the last days of the Soviet regime. During the years 1897–1989 the increase in the role of non-Russians in the ruling structures was due to an increase in their ethno-political status (their IEPR rose from 0.61 to 0.93), for the share of non-Russians in the country's population decreased by 6.5 percentage points over this period. The decline in the percentage of Russians in government accelerated in the years 1979–1989 under the influence of the higher birth rate among non-Russians: the share of Russians in the population fell by 1.6 percentage points, and that of non-Russians increased by 1.6 points. By 1999, only 10 years after the collapse, had the USSR endured and the pace of the dynamics of Russians and non-Russians continued as in the Soviet period, non-Russians would have become the majority, and de-Russification would thereafter have gained strength.

After the disintegration of the Soviet Union this is exactly what took place in the post-Soviet republics. In 1989, there were 286 million people living in the USSR, of whom 145 million or 51% were Russians. In 2018, there were approximately 295 million people in the post-Soviet space, of whom 125 million, or 42%, were Russians2. Just twenty-nine years after the breakup, the total population of the fifteen former union republics increased by about 9 million, the number of Russians decreased by 20 million, and their share fell by 9%. Russians have become a minority. If the USSR had lasted, the depopulation of Russians would have led to a decline in their participation in government bodies. There would also inevitably have been other changes in the national composition of officials, as the population dynamics in individual republics were different. From 1989 to 2019 the population increased by 26.5 million in the six Muslim republics—Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, and decreased by 16.5 million in the republics of the RSFSR, Estonia, Ukraine, Moldova, Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, Georgia and Armenia3 [How the number changed..., 2020].

Another important fact: non-Russian peoples who gained statehood after 1917 expanded their participation in government to a greater extent than non-Russians who did not have statehood. Over the period 1897–1989 in the “national borderlands” the percentage of representatives from fourteen titular nations (excluding Russians) among administrative personnel increased by 39.6 points (from 35.0% to 74.6%) in the years 1897–1989, while the percentage for non-Russian ethnic groups as a whole rose by 20.0 points (from 59.5% to 79.5%). In all the union republics, including the Russian Federation, the displacement of Russians from the governing structures occurred, albeit with varying intensity (Table 7).

Russia experienced the least de-Russification. Over the years 1897–1979 the percentage of the titular nationality (Russians) among officials in Russia decreased from 89.3% to 82.4% (by 1989 to 81.6%), and in the population of the RSFSR the Russian percentage increased from 80.5% to 82.4%. By contrast, the share of non-Russians in the administration rose from 10.7% to 17.6% (by 1989 to 18.4%), mainly due to an increase in their representativeness—their IEPR increased from 0.55 to 1.00. By no later than 1959, they were represented in the power structures in proportion to their number.

The displacement of Russians from the governing entities in the "national borderlands" proceeded more intensively. Already in 1897 the percentage of Russians among officials on the territory of the fourteen union republics under Soviet rule equaled only 40.5%; after 1927 this indicator systematically declined to 20.5% by 1989. Conversely, the role of local cadres in government bodies increased, as their share among officials rose from 59.5% to 79.5%. From 1897 to 1989 the index of representativeness of Russians plummeted by 2.8 times (from 2.89 to 1.02), while that of non-Russians increased by 1.4 times from 0.69 to 0.99. As a result, by 1989 Russians and non-Russians were represented in the power structures at a ratio close to the democratic norm in fourteen union republics (the USSR excluding the RSFSR) as a whole: The IEPR of Russians was equal to 1.02, of non-Russians 0.99. In five of the fourteen union republics (Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Estonia), however, Russians were underrepresented; but the titular ethnic groups prevailed in the power structures in both absolute and percentage terms thanks to their large numbers and controlled the administration in twelve of the fourteen union republics. Only in Kazakhstan and Latvia did they not have a majority, in Kazakhstan due to their small numbers (in 1989 the population share of Kazakhs was 28.6%), and in Latvia due to the underrepresentation of Latvians in the administration (Table 7). Russians were still in the minority in all government bodies in the Kazakh SSR and the Latvian SSR, however.

By 1989 representatives of the titular ethnic group had also taken dominant positions among senior leaders in the production sectors of the country's economy (Table 8). This happened gradually as the number of national personnel grew. In 1926, in addition to Russians, only two ethnic groups, the Armenians and Georgians, were prevalent among the economic administrators of the titular republics. In 1959, the number of such ethnic groups increased to seven, and in 1979 to nine. In 1989, only Kazakhs were not in the majority, for their percentage in the population of the republic was 39.7%.

Tab. 7

De-Russification of governance in the Union Republics in 1917-1989.

| Republic of the USSR, nation | Representativeness index | The share of the ethnic group in management (in %) | ||||||||

| 1897 | 1926 | 1959 | 1979 | 1989 | 1897 | 1926 | 1959 | 1979 | 1989 | |

| RSFSR: Russians | 1,11 | 1,10 | 1,00 | 1,00 | 1,01 | 89,3 | 81,8 | 82,5 | 82,4 | 81,6 |

| Non-Russians | 0,55 | 0,70 | 1,02 | 1,00 | 0,97 | 10,7 | 18,2 | 17,5 | 17,6 | 18,4 |

| Azerbaijan SSR : | ||||||||||

| Azerbaijanis | – | 0,84 | 0,94 | 1,04 | 1,03 | – | 49,0 | 56,1 | 77,9 | 83,3 |

| Russians | 3,35 | 1,43 | 1,18 | 0,86 | 0,79 | 84,3 | 17,5 | 17,2 | 8,4 | 5,3 |

| Armenian SSR: Armenians | 0,83 | 1,14 | 1,06 | 1,05 | 1,03 | 39,3 | 94,5 | 92,4 | 94,4 | 97,0 |

| Russians | 3,52 | 0,50 | 0,72 | 0,49 | 0,75 | 23,4 | 1,2 | 2,7 | 1,4 | 1,3 |

| Belarusian SSR: Belarusians | 0,70 | 0,69 | 0,85 | 0,93 | – | 30,7 | 57,5 | 69,5 | 72,5 | – |

| Russians | 4,50 | 2,18 | 3,10 | 1,50 | – | 42,0 | 16,6 | 20,7 | 19,0 | – |

| Georgian SSR: Georgians | 0,67 | 1,08 | 1,11 | 1,11 | 1,11 | 50,2 | 69,5 | 72,0 | 76,5 | 79,2 |

| Russians | 5,24 | 1,91 | 0,70 | 0,66 | 0,66 | 32,5 | 8,0 | 7,5 | 5,2 | 4,3 |

| Kazakh SSR: Kazakhs | 0,23 | 0,42 | 1,57 | 1,45 | – | 16,2 | 24,7 | 38,3 | 41,5 | – |

| Russians | 3,46 | 2,74 | 0,96 | 0,90 | – | 77,8 | 51,2 | 43,6 | 40,7 | – |

| Kyrgyz SSR: Kyrgyz | 0,15 | 0,35 | 1,00 | 1,17 | – | 11,7 | 24,1 | 38,5 | 47,4 | 51,0* |

| Russians | 6,82 | 4,38 | 1,14 | 1,05 | – | 78,1 | 45,9 | 36,9 | 33,4 | – |

| Latvian SSR: Latvians | 0,36 | – | 0,78 | 1,04 | 0,95 | 15,9 | – | 48,5 | 51,9 | 46,8 |

| Russians | 4,17 | – | 1,48 | 1,00 | 1,06 | 29,6 | – | 37,9 | 34,6 | 36,5 |

| Lithuanian SSR: Lithuanians | 0,40 | – | 0,87 | 1,00 | 0,98 | 11,9 | – | 69,5 | 77,3 | 75,9 |

| Russians | 5,09 | – | 2,53 | 1,28 | 1,33 | 48,4 | – | 19,9 | 13,0 | 13,3 |

| Moldavian SSR: Moldovans | 0,25 | – | 0,56 | 0,81 | – | 10,2 | – | 37,7 | 50,4 | – |

| Russians | 2,33 | – | 3,60 | 1,71 | – | 76,0 | – | 30,9 | 22,5 | – |

| Tajik SSR: Tajiks | 0,87 | 0,55 | 1,00 | 1,07 | – | 23,8 | 40,4 | 50,3 | 56,7 | – |

| Russians | 11,83 | 13,00 | 1,48 | 1,25 | – | 49,7 | 35,0 | 23,3 | 18,3 | – |

| Turkmen SSR: Turkmens | 0,20 | 0,36 | 0,85 | 1,01 | – | 10,6 | 25,7 | 47,9 | 62,8 | – |

| Russians | 4,09 | 6,35 | 1,32 | 1,16 | – | 69,6 | 46,2 | 28,9 | 19,9 | – |

| Uzbek SSR: Uzbeks | 0,28 | 0,60 | 0,83 | 0,96 | 0,96 | 15,8 | 40,6 | 49,5 | 61,1 | 64,6 |

| Russians | 11,83 | 6,19 | 1,47 | 1,20 | 1,25 | 49,7 | 49,2 | 23,4 | 17,3 | 13,6 |

| Ukrainian SSR: Ukrainians | 0,73 | 0,66 | 0,87 | 0,97 | – | 53,3 | 55,0 | 68,1 | 70,0 | – |

| Russians | 3,23 | 2,75 | 1,62 | 1,14 | – | 38,9 | 23,0 | 25,2 | 25,1 | – |

| Estonian SSR: Estonians | 0,62 | – | 0,89 | 1,12 | 1,00 | 52,4 | – | 66,1 | 66,9 | 58,5 |

| Russians | 3,72 | – | 1,37 | 0,81 | 0,98 | 28,3 | – | 26,4 | 25,1 | 31,2 |

| USSR: Russians | 1,43 | 1,22 | 1,14 | 1,07 | 1,06 | 67,8 | 64,8 | 61,2 | 59,1 | 56,2 |

| Non-Russians | 0,61 | 0,76 | 0,84 | 0,91 | 0,93 | 32,2 | 35,2 | 38,8 | 40,9 | 43,8 |

| 15 titular nations | 1,06 | 0,96 | 0,97 | 1,00 | 1,01 | 85,3 | 82,9 | 90,1 | 90,3 | 90,1 |

| The USSR excluding the RSFSR: Russians | 2,89 | 1,67 | 1,65 | 1,11 | 1,02 | 40,5 | 27,9 | 25,0 | 23,7 | 20,5 |

| Non-Russians | 0,69 | 0,87 | 0,88 | 0,97 | 0,99 | 59,5 | 72,1 | 75,0 | 76,3 | 79,5 |

| 14 titular nations | 0,63 | 0,93 | 0,89 | 0,99 | 1,02 | 35,0 | 82,2 | 61,8 | 69,9 | 74,9 |

Tab. 8

Representatives of the titular nation among senior managers in the production sectors of the national economy, 1926-1989 (%)

| Republic, nation | 1926 | 1959 | 1979 | 1989 | Change during the period 1926–1989 |

| RSFSR: Russians | 82,6 | 81,0 | 83,4 | 77,3 | –5,3 |

| Non-Russians | 17,4 | 19,0 | 16,6 | 22,7 | +5,3 |

| Azerbaijan SSR: Azerbaijanis | 17,8 | 49,0 | 73,5 | 93,8 | +76,0 |

| Armenian SSR: Armenians | 93,1 | 92,4 | 94,4 | 99,4 | +6,3 |

| Belarusian SSR: Belarusians | 40,6 | 59,3 | 71,6 | 77,7 | +37,1 |

| Georgian SSR: Georgians | 58,2 | 72,7 | 83,2 | 89,3 | +31,1 |

| Kazakh SSR: Kazakhs | 10,6 | 19,3 | 25,4 | 39,5 | +28,9 |

| Kyrgyz SSR: Kyrgyz | 6,9 | 20,3 | 29,6 | 55,1 | +48,2 |

| Latvian SSR: Latvians | – | 50,1 | 51,3 | 63,1 | +13,0* |

| Lithuanian SSR: Lithuanians | – | 71,4 | 81,8 | 91,5 | +20,1* |

| Moldavian SSR: Moldovans | – | 21,9 | 43,7 | 50,0 | +27,9* |

| Tajik SSR: Tajiks | 22,9 | 30,1 | 38,8 | 66,3 | +43,4 |

| Turkmen SSR: Turkmens | 9,9 | 32,0 | 53,2 | 71,8 | +61,9 |

| Uzbek SSR: Uzbeks | 19,8 | 34,4 | 42,8 | 67,6 | +47,8 |

| Ukrainian SSR: Ukrainians | 40,4 | 57,9 | 66,7 | 79,0 | +38,6 |

| Estonian SSR: Estonians | – | 74,4 | 71,1 | 82,2 | +7,8* |

Tab. 9

The index of ethnopolitical representativeness among senior managers in the production sectors of the national economy

| Republic, nation | 1926 | 1959 | 1979 | 1989 | Change during 1926–1989 |

| RSFSR: Russians | 1,08 | 0,98 | 1,01 | 0,95 | –0,13 |

| Non-Russians | 0,73 | 1,11 | 0,95 | 1,23 | 0,49 |

| Azerbaijan SSR: Azerbaijanis | 0,31 | 0,82 | 0,98 | 1,13 | 0,83 |

| Armenian SSR: Armenians | 1,12 | 1,06 | 1,05 | 1,07 | –0,06 |

| Belarusian SSR: Belarusians | 0,48 | 0,72 | 0,92 | 1,00 | 0,51 |

| Georgian SSR: Georgians | 0,90 | 1,12 | 1,20 | 1,27 | 0,37 |

| Kazakh SSR: Kazakhs | 0,18 | 0,79 | 0,88 | 0,99 | 0,81 |

| Kyrgyz SSR: Kyrgyz | 0,10 | 0,53 | 0,73 | 1,05 | 0,95 |

| Latvian SSR: Latvians | – | 0,80 | 1,03 | 1,21 | 0,41* |

| Lithuanian SSR: Lithuanians | – | 0,90 | 1,06 | 1,15 | 0,25* |

| Moldavian SSR: Moldovans | – | 0,32 | 0,70 | 0,77 | 0,45* |

| Tajik SSR: Tajiks | 0,31 | 0,60 | 0,73 | 1,06 | 0,75 |

| Turkmen SSR: Turkmens | 0,14 | 0,57 | 0,82 | 1,00 | 0,86 |

| Uzbek SSR: Uzbeks | 0,26 | 0,58 | 0,82 | 0,95 | 0,69 |

| Ukrainian SSR: Ukrainians | 0,97 | 0,74 | 0,92 | 1,09 | 0,12 |

| Estonian SSR: Estonians | – | 1,00 | 1,19 | 1,34 | 0,34* |

In Moldova, the titular people accounted for about half of the managers, but together with representatives of other non-Russian peoples their share reached more than 70%. The growth dynamics of the economic elite were positive: on average, the share of top managers from the titular ethnicity increased by 35 percentage points among fourteen nations. The largest increase was observed among the peoples with a low starting position—Azerbaijanis (76 points) and Turkmen (61.9 points), and the smallest among the peoples with a high starting point—Armenians (6.3 points) and Estonians (7.8 points). Only in the RSFSR did the percentage of titular Russian managers decrease by 5.3 points. Because of this, an equalization of ethnic statuses occurred, which is evident from the data on the ethnic representativeness of different peoples in the economic elite (Table 9). A national elite has also developed or emerged in the non-productive spheres of the national economy (finance, trade, etc.), as well as in culture and science, education and medicine, and the like [Public education..., 1989: 16, 202, 237, 256].

The study allows us to draw the following conclusions. Non-Russian ethnic groups were represented in the governing structures long before the revolution of 1917, although at a ratio below the democratic proportion. But their underrepresentation, excluding Jews, was mainly due to a shortage of national personnel and poor knowledge of the Russian language, rather than legal restrictions on engaging in government service; that is, it is incorrect to consider the situation political discrimination [Mironov, 2010: 148-152]. Indigenization (korenizatsiia) or, as it was also known, nationalization of the administration took place until the last days of Soviet rule. Ukrainization, Belarusization, Bashkirization, Turkmenization, Uzbekization, Tatarization, Yakutization, and the like were supported by the Center and at all levels of government as democratic and progressive processes. Russification was considered a manifestation of great-power chauvinism. Because of this, in the period 1897–1990 as a whole the role of non-Russian ethnic groups in the power structures in the entire country increased steadily, while the role of Russians decreased. The reverse side of indigenization was the de-Russification of governance not only in the Soviet Union in its entirety but also in all the union and autonomous republics. The Russian Federation was the least affected by the de-Russification, which occurred with the greatest intensity in the "national borderlands". By 1979, non-Russians and Russians were represented in the governing bodies of all the union republics at a level close to the democratic norm, but due to the large populations of titular ethnic groups, they were prevalent in the power structures both absolutely and relatively. In 1989, in nine of the fifteen union republics, native peoples had a qualified majority, which means that according to the republican constitutions, they had the opportunity to adopt any laws and carry out any reforms. In Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan and Estonia, the titular peoples had a simple majority; only in Kazakhstan (due to their small numbers) and in Latvia (due to the underrepresentation of Latvians in the administration) did the titular ethnicity fail to have a majority. In these two republics, however, Russians were still in the minority in the power structures, and in terms of the share of managers they were inferior to the titular ethnicities.

The collapse of the Soviet Union had objective prerequisites formed under the influence of the nationalities policy of the Center, which aimed to establish governance and to equalize the levels of development of the union republics, ensuring their accelerated development, at the expense of the most developed and resource-rich republics, primarily the RSFSR. The comprehensive progress of the republics contributed objectively to the emergence and development of educated and qualified national cadres. Moscow stimulated the formation of modern national elites in the republics by indigenizing, or nationalizing, the administration. Meanwhile, a national elite, a state apparatus and a governing class are rightly considered attributes of any national state. Given a territory (with recognized borders and a population), state symbols and a constitution (which in 1924 gave to the union republics sovereignty and the right to self-government up to secession), by 1979 the republics began to possess all the attributes of a real state, and the titular ethnic groups became true nations. In cases of political desire or necessity the union republics could separate from the USSR and exist independently. Thereafter, the fate of the Soviet Union was left to the mercy of local elites and depended on a conjuncture of circumstances. The decisive issue was the real and imagined benefits (in a broad sense) and the attractiveness of separation or union. The republics developed rapidly within the framework of a single state in the period of the rise, stability and prosperity of the Soviet Union; but in the exceptional conditions of the crisis of the Soviet system in the 1980s, the national elites had both a real opportunity and the temptation to secede, to find their own way out of the crisis and their own way to prosperity. The expansion of nationalism that pushed the republics to secession occurred as a result of the political mobilization of ethnic groups, a mobilization carried out by national elites. "The USSR disintegrated not so much as the result of the action of certain historical laws and the desire of peoples for national self-determination," V. A. Tishkov declared in the early 1990s, "but as a result of a deep split within the Soviet elite, individual groups of which first of all determined themselves" [Tishkov, 1996: 37]. One must agree with researchers who argue that Soviet nationalities policy, following an essentially multicultural model, objectively created a set of institutions and agencies that contributed to the emergence and development of nation-states, which, if necessary, could secede from the USSR [Tishkov, 1994: 9; Tishkov, Shabaev, 2011: 154-155; Burovsky, 2004: 214-215; Martin, 2011: 32; Hirsch, 2005; Lane, 1996; Slezkine, 1994: 414-452; Walker, 2003: 193-202]. Thus, the Center created the structural prerequisites for and the possibility of the country's collapse with its own hands. The motivation in different periods varied: to attract the non-Russian peoples, who felt aggrieved/slighted/disenfranchised before the revolution, to the side of the Bolsheviks; to spark world revolution; to draw the divergent “national borderlands” of the empire into a single state; to weaken interethnic conflicts; to create in the localities/at the grassroots level a competent administrative apparatus that was loyal to the Center; and others [Amanzholova, Krasovitskaya, 2020: 96-172]. This conscious rejection of the idea of a single nation based on common citizenship in favor of nation-states stimulated first the development of nationalism in the republics, and second, created a national track, which it was extremely difficult to leave in later years.

Hence the doubts about the viability of the Soviet project of nation-state building, which aimed, as is sung in the Soviet anthem, to create a "single, powerful, unbreakable Union" of "free republics". The task of creating free republics was successfully completed. But the country's leadership did not find a mechanism for reconciling the interests of the free republics it had created in a single multinational state for the long term [Toshchenko, 2003: 53, 121], although it had tactical successes in the short and medium term. The nationalization of interethnic relations led to the sovereignization of the union republics, which became a key element, but not the only factor, in the breakup of the USSR. The disintegration of the Soviet Union was not an accident, but a process, not a collapse caused mainly by the mistakes of the perestroika period, but the natural result of Soviet nationalities policy and the immanent desire of national elites for sovereignty, which guaranteed them full power over the resources and population of the of a republic.

Библиография

- 1. AllUnion Population Census of 1926: in 56 vols. (1928–1930) Vols 18–34. Moscow. (In Russ.)

- 2. AllUnion Population Census of 1959. Russian State Archive of Economics (RSAE). Archive 1562 “Central Statistical Office of the USSR”. List of files 336. Documents 2839, 2871–2890, 2893, 2898, 2904, 2924, 2928, 2938, 2939, 2949.

- 3. AllUnion Population Census of 1979. RSAE. Archive 1562. List of files 336. Documents 7466–7473, 7490, 7500, 7501, 7503, 7505, 7508, 7510.

- 4. All–Union Population Census of 1989. RSAE. Archive 1562. List of files 69. Documents 2570–2578. Amanzholova D.A., Krasovitskya T.Yu. (2020) Cultural Complexity of Soviet Russia: Ideology and Management Practices, 1917–1941. Moscow: Novyi khronograf. (In Russ.)

- 5. Artemyev A.P. (1975) Fraternal Combat Union of the Peoples of the USSR in the Great Patriotic War. Moscow: Mysl’. (In Russ.)

- 6. Arutyunyan Yu.V. (ed.) (1992) Russian: Ethnosociological Essays. Moscow: Nauka.

- 7. Arutyunyan Yu.V., Drobizheva L.M. (2016) Passed Paths and Some Problems of Modern Russian Ethnosociology. In: Ostapenko L.V., Subbotina I.A. (eds) Ethnosociology Yesterday and Today. Moscow: IEA RAN: 29–38. (In Russ.)

- 8. Beissinger M.R. (2002) Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- 9. Brubaker R. (1994) Nationhood and the National Question in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet Eurasia: An Institutional Account. Theory and Society. Vol. 23. No. 1: 47–78. DOI: 10.1007/BF00993673.

- 10. Burovskii A. M. (2004) The Collapse of the Empire: The Course of Unknown History. Moscow: AST. (In Russ.) Drobizheva L.M. (ed.) (1995) А Conflict Ethnicity and Ethnic Conflicts. Moscow: IEA RAN. (In Russ.) Drobizheva L.M. (ed.) (1998) Asymmetric Federation: Looking from the Center, Republics and Regions. Moscow: IS RAN. (In Russ.)

- 11. Drobizheva L.M. (ed.) (1996) Democratization and Images of Nationalism in the Russian Federation in 90s. Moscow: Mysl’. (In Russ.)

- 12. Drobizheva L.M. (ed.) (1998) Social and Cultural Distances: The Experience of Multinational Russia. Moscow: IS RAN. (In Russ.)

- 13. Drobizheva L.M. (ed.) (2002) Social Inequality of Ethnic Groups: Representations and Reality. Moscow: Academia. (In Russ.)

- 14. Drobizheva L.M. (2003) Social Problems of Interethnic Relations in PostSoviet Russia. Moscow: TsOTs. (In Russ.)

- 15. Drobizheva L.M. (ed.) (1994) Values and Symbols of Ethnic SelfAwareness. Moscow: IEA RAN. (In Russ.) Drobizheva L.M., Guzenkova T.S. (eds) (1995) Sovereignty and Ethnic SelfConsciousness: Ideology and Practice. Moscow: IEA RAN. (In Russ.)

- 16. Fedorchenko S.N. (2010) The Problem of Quotas in the Russian State Personnel Policy. In: National Security: The Scientific and State Management Content: Proceedings of the all-Russian Scientific Conference. December 4, 2009. Moscow: Nauchnyi Ekspert: 692–705. (In Russ.)

- 17. General Summary across the Empire of the Results of the Compilation of Data of the First General Population Census, Carried out on January 28, 1897: in 2 vols. (1905) Vol. 2. St. Petersburg: Tip. N.L. Nyrkina. (In Russ.)

- 18. Hirsch F. (2005) Empire of Nations: Ethnographic Knowledge and the Making of Soviet Union. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- 19. Informal Ethnic Quotas in the MultiEthnic Republics of the North Caucasus: Analytical Report. (2017) Makhachkala. (In Russ.)

- 20. Lane D. (1996) The Gorbachev Revolution: The Role of the Political Elite in Regime Disintegration.

- 21. Political Studies. Vol. 44. No. 1: 4–23. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00754.x.

- 22. Martin T. (2011) The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923– 1939. Moscow: ROSSPEN. (In Russ.)

- 23. Mironov B.N. (2017) Management of Ethnic Diversity in the Russian Empire. St. Petersburg: Dmitriy Bulanin. (In Russ.)

- 24. Mironov B.N. (2021) Disintegration of the USSR in Historiography: Collapse or Dissolution. Vestnik Sankt Peterburgskogo universiteta. Istoriya [Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. History]. Vol. 66. Iss. 1: 132–147. DOI: 10.21638/11701/spbu02.2021.108. (In Russ.)

- 25. Mironov B.N. (2018) The Russian Empire: From Tradition to Modernity: in 3 vols. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. St. Petersburg: Dmitriy Bulanin. (In Russ.)

- 26. National Economy of the USSR in 1989. (1990) Moscow: Finansy i Statistika. (In Russ.)

- 27. Public Education and Culture in the USSR: Statistics Digest. (1989) Moscow: Finansy i statistika. (In Russ.)

- 28. Results of the allUnion Population Census of 1970: in 10 vols. (1973) Vol. 8. Part 1. Moscow. (In Russ.)

- 29. Slezkine Y. (1994) The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism. Slavic Review. Vol. 53. No. 2: 414–452. DOI: 10.2307/2501300.

- 30. The Labor in the USSR (statistics digest). (1988) Moscow: Finansy i statistika. (In Russ.)

- 31. Tishkov V.A. (1996) Conceptual Evolution of National Policy in Russia. Moscow: IEA RAN. (In Russ.) Tishkov V.A. (1997) Essays on the Theory and Politics of Ethnicity in Russia. Moscow: Russkiy Mir. (In Russ.) Tishkov V.A. (1994) Nationalities and Nationalism in the Post-Soviet Space: Historical Aspect. In:

- 32. Tishkov V.A. (ed.) Ethnicity and Power in MultiEthnic States: Proceedings of the International Conference [January, 25–27], 1993. Moscow: Nauka: 9–34. (In Russ.)

- 33. Tishkov V.A., Shabaev Yu.P. (2011) Ethnopolitology: Political Functions of Ethnicity. Moscow: Moskovsk. un-t. (In Russ.)

- 34. Toshchenko Zh.T. (2003) Ethnocracy: History and Modernity (Sociological Essays). Moscow: ROSSPEN. (In Russ.)

- 35. Walker E.W. (2003) Dissolution: Sovereignty and the Breakup of the Soviet Union. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Publ. Policy Press.